Feature

Investigating Elementary Preservice Teachers’ Beliefs About Teaching and Learning Science

Journal of College Science Teaching—May/June 2022 (Volume 51, Issue 5)

By Ezgi Yesilyurt

To inform teacher education programs, it is imperative to uncover preservice teachers’ (PSTs) implicit and tacit beliefs about teaching and learning science. The study of teachers’ beliefs requires a range of methodological approaches to unearth their tacit beliefs. In that regard, this study used metaphor construction in conjunction with drawing tasks to examine PSTs’ beliefs about teaching and learning science. A total of 129 preservice elementary teachers were asked to construct metaphors and drawings characterizing science teaching and learning. The findings indicated that even though PSTs had predominantly teacher-centered beliefs, they adopted several aspects of student-centered teaching perspectives. Furthermore, the PSTs appeared to be unaware of or to have underestimated the importance of learners’ existing knowledge in learning science.

Increasing attention is being given to teachers’ beliefs since the paradigm shift in education from behaviorism to constructivism. The Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS; NGSS Lead States, 2013) adopt the learner-centered approach to teaching science that emphasizes students’ learning of disciplinary core ideas and crosscutting concepts by actively engaging in science and engineering practices. This approach is based on the constructivist philosophy of teaching and learning.

According to constructivist theory, learners do not come into the educational system with empty minds, but rather with prior knowledge and beliefs. The constructivist view also asserts that individuals’ actions are mainly shaped by their beliefs, which are derived from their earlier experiences. Likewise, preservice teachers enter teacher training programs with established beliefs about teaching and learning, which have been influenced and shaped mainly by their previous schooling experiences (e.g., Borko & Putnam, 1996; Friedrichsen & Dana, 2003). Along with this line of thinking, teacher education researchers investigated the beliefs that may influence teachers’ pedagogical practices (Pajares, 1992). A considerable number of studies have reported that teachers’ perspectives on teaching and classroom practices are influenced by beliefs about teaching and learning that are deeply rooted in their minds (e.g., Pajares, 1992). In fact, those beliefs function as a filter through which teachers guide their instructional decisions and subsequent classroom practices (Borko & Putnam, 1996; Pajares, 1992). Teacher educators must therefore uncover preservice teachers’ implicit and tacit beliefs about teaching and learning in order to inform their curriculum and program directions.

Belief as an experience-driven psychological construct can be defined as understandings, propositions, or premises about the world that an individual accepts to be true (Kagan, 1992; Pajares, 1992). Kagan (1992) regarded teachers’ beliefs as sometimes unconsciously held assumptions concerning teaching, learning, schooling, and educational materials. Past studies on beliefs about teaching and learning examined teachers’ beliefs in two main categories: learner-centered (progressive model) and teacher-centered beliefs (traditional model). Teacher-centered beliefs are typically associated with teaching approaches that focus on the transmission of subject matter knowledge from teachers to students, while learner-centered beliefs relate to teaching approaches that focus on promoting learning environments in which students can take an active role and construct their own knowledge.

The current standards call for adaptation of teachers’ beliefs about teaching and learning science to align their instructional practices with the constructivist philosophy underpinning the standards. Even though the research on teachers’ beliefs about teaching and learning science is expanding, the focus of this line of research has been mostly on the middle or high school level. On the other hand, the elementary level is an important stage where teachers set the foundations of scientific understanding and habits of mind for their students. With this in mind, the study discussed in this article aimed to examine elementary preservice teachers’ (PSTs) perceived beliefs about teaching and learning science in order to expand our understanding of teachers’ beliefs.

Kagan (1992) argued that teachers are sometimes not aware of their own beliefs, do not have the language to explain and categorize their beliefs, or are often unwilling to explicitly express these beliefs, so different methodological approaches should be adopted to unearth teachers’ implicit beliefs. This study used multiple instruments to explore preservice teachers’ beliefs about teaching and learning science.

Instruments to uncover beliefs about teaching and learning

Studies indicated that metaphor construction and drawing tasks can be effective cognitive tools for enabling researchers to uncover teachers’ beliefs about teaching and learning science that are nested in their overall belief system (e.g., Buaraphan, 2011; Saban et al., 2007; Soysal & Radmard, 2017).

Ever since conceptual metaphors were first introduced as cognitive tools that individuals use to describe their experiences (Lakoff & Johnson, 1980; Lakoff, 1993), many studies have attempted to use metaphors to identify teachers’ tacit beliefs about their professions (e.g., Buaraphan, 2011; Saban et al., 2007). Metaphors are symbols of connection between two dissimilar concepts and are constructed using one domain of experience (source domain) to argue for another (target domain; Lakoff & Johnson, 1980). Lakoff and Johnson (1980) explained this as follows: “Most of what we think, experience and do is very much a matter of metaphor” (p. 3). They emphasized that metaphors are manifestations of the underlying conceptual structure of the human mind. Individuals sometimes use metaphors that lie beneath the surface of their awareness as a basis for framing their life experiences (Buaraphan, 2011).

Metaphors could therefore facilitate the identification of underlying and implicit assumptions and beliefs that literal language cannot articulate (Aubusson & Webb, 1992; Gurney, 1995). For instance, Aubusson and Webb (1992) indicated that even though teachers self-reported their teaching beliefs as learner-centered, their teaching metaphors indicated that their beliefs were aligned with teacher-centered approaches. Much of the earlier work mainly used metaphor construction tasks to investigate teachers’ general beliefs about teaching; however, little attention is given to content-specific beliefs in this line of research (e.g., Buaraphan, 2011). The proposed study used the metaphor construction task to examine PSTs’ beliefs about teaching and learning science.

Along with the teachers’ metaphors, the study used written questions, as well as teachers’ drawings of themselves as a science teacher, to further examine the PSTs’ beliefs about teaching and learning science. Over the past 2 decades, many scholars have used drawings or illustrations as a method of research to explore individuals’ mental models, which highlight their implicit beliefs (e.g., Moseley et al., 2010; Thomas et al., 2001; Weber & Mitchell, 1996). Mental models represent the reality that individuals construct in their minds to interpret their experiences and make sense of the world around them (Coll & Treagust, 2003). From the cognitive science perspective, Norman (1983) asserted that mental models reflect our belief systems, which are obtained through observations and inferences we make or instructions we receive. Individuals’ views of their own capabilities and the task they are required to perform influenced their prior conceptualizations, which eventually shape their internal, mental models of themselves and their interactions with their surroundings (Norman, 1983). Barnes (1992) referred to mental models as frames of expectations and proposed that teachers’ professional frames—which are formed by their past experiences and their values and expectations—have an impact on how teachers perform their teaching practices. Teachers’ mental models and frames indicate their beliefs about teaching, and those models can be used to predict human behaviors (e.g., classroom practices). Along with this line of thinking, the task of drawing oneself as a teacher has the potential to reflect the mental models that teachers have in their minds. The task of drawing oneself as a teacher has been shown to provide insights into teachers’ beliefs about teaching and learning science (e.g., Minogue, 2010; Weber & Mitchell, 1996). In this study, the PSTs’ drawings were used to increase the validity of the metaphor analysis. The Draw-a-Science-Teacher-Test (DASTT; Thomas et al., 2001), which was designed to explore student-centered and teacher-centered teaching beliefs, was used in this study.

Methodology

Participants

The participants included 145 preservice elementary teachers who were enrolled in a science teaching methods course in the southwestern United States. Participants were all in their senior year of the elementary education program and ranged in age from 20 to 59 years old, with a mean age 26.16. The state where the university is located had adopted the NGSS for K–12 science education.

Data collection and analysis

The main data source in this study was the PSTs’ self-constructed metaphors. The open-ended questions concerning teachers’ beliefs and drawings were used to triangulate the data derived from the PSTs’ metaphors. The data were collected across four semesters from two sections in the science methods course to explore the PSTs’ written responses, drawings, and metaphors used to describe their beliefs about teaching and learning science. At the beginning of each semester, the PSTs were asked to complete a survey that consisted of three sections: two open-ended questions related to their views on in what ways students learn science; the drawing task, which required the PSTs to draw themselves while teaching science and explain what the teacher and students are doing; and the metaphor construction task, which required them to write metaphors characterizing a teacher’s and student’s role in teaching and learning science. The structured prompts (e.g., “A teacher is like ___ because ___”; “A student is like ___ because ___”; Soysal & Radmard, 2017) were used to capture PSTs’ justifications.

The data were inductively analyzed using the MAXQDA qualitative analysis software to develop the initial thematic structure and enhance the accuracy of the analysis. Thematic analysis was used to identify emerging themes by generating initial common themes and, later, conceptual categories (Braun & Clarke, 2006). To establish the inter-rater reliability, the data were coded independently by two experts, and the inter-coder agreement was established as 0.89 (κ = 0.89, p < 0.0005).

Findings

A total of 12 conceptual themes emerged from the metaphors constructed by participants. The emerging themes were examined and compared across PSTs’ drawings and views of teaching and learning science and then were assigned to three major categories: teacher-centered beliefs, “mixed” beliefs, and student-centered beliefs (see Table 1). Teacher-centered beliefs referred to the metaphors (and drawings) that indicated teachers were knowledge holders, knowledge providers, and authoritative figures and the students were recipients of knowledge and passive actors in the processes of teachers’ teaching. “Mixed” beliefs—reflecting aspects of both teacher-centered and student-centered teaching perspectives—referred to the metaphors (and drawings) that indicated teachers were team leaders who led classroom actions and students were active participants (although limited) in their learning processes. Student-centered beliefs referred to the metaphors that implied teachers played the role of facilitator or guide in students’ learning processes; in this category, students were mostly positioned by the PSTs as the main figure in the learning process (e.g., explorer, leader, teacher, etc.).

Of the teaching metaphors constructed by the PSTs, 39.31% indicated the use of teacher-centered teaching approaches, while 33.1% of the metaphors were associated with student-centered teaching approaches and 27.59% reflected “mixed” teaching beliefs.

In this study, it was found that the PSTs holding teacher-centered beliefs viewed teachers as knowledge providers (teacher as a nurturer). Consider the following metaphor provided by a participant PST: “Teachers are like water because they pour all of the knowledge on the students to help them grow.” Participant PSTs also viewed students as immature organisms who need teachers’ knowledge to grow (learn). For instance, one PST stated, “A student is like a seed because the student blooms just like a seed blooms from the water.”

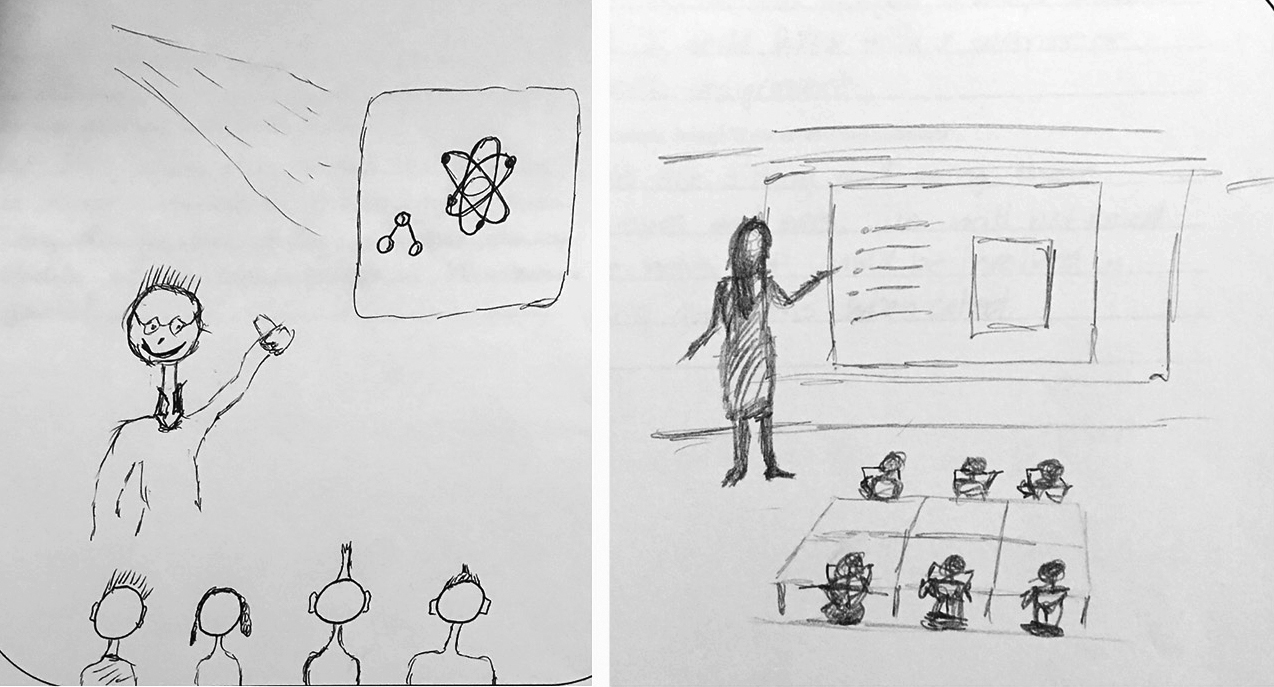

This study also indicated that the PSTs positioned teachers as the sole owner of knowledge (teacher as a source). One PST, for example, stated, “A teacher is like a website because they present all information, and if it is not in the right code, then no one can get information from it.” They also viewed students as the passive recipients of knowledge: “A student is like a computer user because they visit the website to learn, and if they don’t understand the information, they find they won’t retain it.” In the teacher-centered beliefs category, several of the participant teachers (n = 7) used the textbook as a metaphor to indicate teachers’ role as a source of knowledge in the teaching and learning process. Consider the following example: “A teacher is like an open book because it gives all the knowledge they have.” They added, “A student is like a sponge because it absorbs the knowledge [that] they receive every day.” The PSTs also perceived teachers as authoritative leaders who control the teaching and learning process, as demonstrated by the following metaphor shared by a participant teacher: “A teacher is like a shepherd because she leads her sheep well and teaches them where they need to go.” They also considered students as the passive followers of the leadership that teachers provide: “A student is like a sheep because he or she follows their shepherd’s footsteps and trust her.” In the category of the teacher as a performer, the PSTs considered teachers the main character of the teaching process, as the following metaphor indicates: “A teacher is like a magician because at times you have to magically create something out of nothing and leave all who witness astonished and memorized.” In this scenario, students are the passive watchers of their teacher’s performances. Consider the following example from a participant PST: “Students are like audiences—they watch in awe as the teacher performs.” Consistent with how they viewed teachers’ metaphorical roles, the PSTs drew teachers in front of the class providing direct instructions (see Figure 1).

Drawings reflecting the teacher-centered approach.

Note. In Figure 1A, the teacher is discussing molecules and atoms. Soon the teacher will ask how these relate to previous lessons on matter. The students are listening to the instruction, taking notes, and drawing the atom models in their science journal. In Figure 1B, the teacher is using direct instruction. She is teaching a science concept and providing basic information, as well as asking questions. The tablets are there for students to take notes.

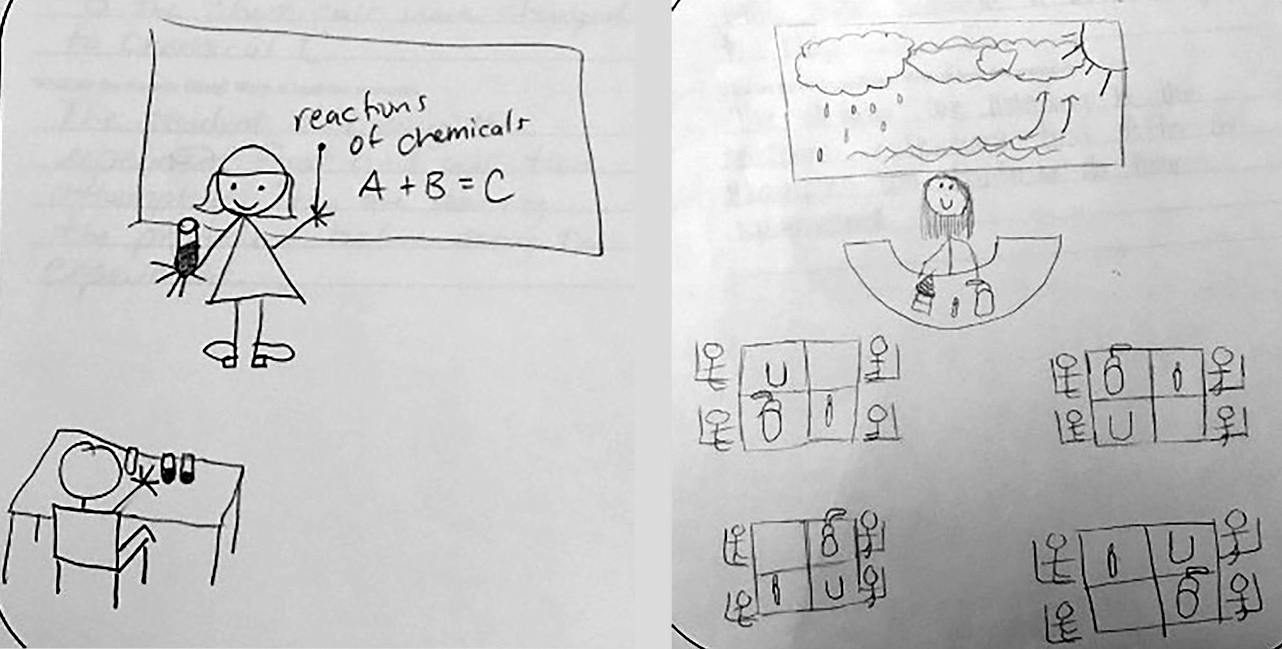

In contrast to the teacher-centered approach, in the “mixed” beliefs category, the majority of teachers (86%) emphasized the use of hands-on activities or learning by doing as the most effective ways to learn science and stated that they were willing to provide their students learning opportunities such as constructing their own hypothesis, engaging in activities, and generating their own conclusions. However, as their metaphors revealed, the PSTs perceived that students’ learning was still under the control of the more knowledgeable teacher (teacher as a team leader). For instance, one PST stated, “The teacher is like a captain because they lead the lesson for the class” and “a student is like a sailor because they follow the guidance of the captain.” Consistent with their metaphors, the drawings of the PSTs in this category further showed that classroom tenets are established by more knowledgeable teachers and followed by students, even though learners have some opportunities to participate in their learning process (see Figure 2). In addition, most of the metaphors in this category showed inconsistencies regarding teachers’ belief systems. For instance, one PST conceptualized the teacher as a guide who allows students’ participation through guided inquiry. On the other hand, the student metaphor positions teachers as a knowledge provider and the owner of the knowledge: “A teacher is like a captain because they guide their students’ path to learning (scaffolding)” and “student is like a sponge because they absorb all the information that teachers have.” Likewise, even though a participant depicted the teacher as a facilitator in her drawing, the metaphor used to describe the teacher’s role indicated that the PST perceived the teacher as the source of knowledge: “A teacher is like a candle because it lights itself till the end to give light (knowledge) to the students.” Within this category, the PSTs also perceived the teacher as a nurturer who provided support and knowledge for students’ learning. Consider the following metaphor: “A teacher is like a gardener because they continue to nourish the seeds (students) until they blossom.” Once again, students were portrayed as immature organisms that need a teacher’s support for learning; without the teacher’s support, they cannot continue their learning process. For instance, one PST stated, “A student is like a seed because they need support from the gardener (teacher) in order to blossom.” In this category, students were not just passive recipients of knowledge, but rather they participated in the learning process as well. However, the students were not fully in charge of their learning since the PSTs in this category still perceived teachers as the only source of knowledge that students would need for the learning process.

Drawings indicating “mixed” teaching approaches.

Note. In Figure 2A, the teacher is demonstrating what each chemical is doing. The students are observing the experiment first, then they will attempt to do it themselves. They are learning the procedure and expectations for doing the experiment, and they have questions about what will happen. In Figure 2B, the teacher is showing an example of what she wants her students to do. After she sets the example, she walks around to help students. Students listen to the teacher’s instructions first, then do their own experiment.

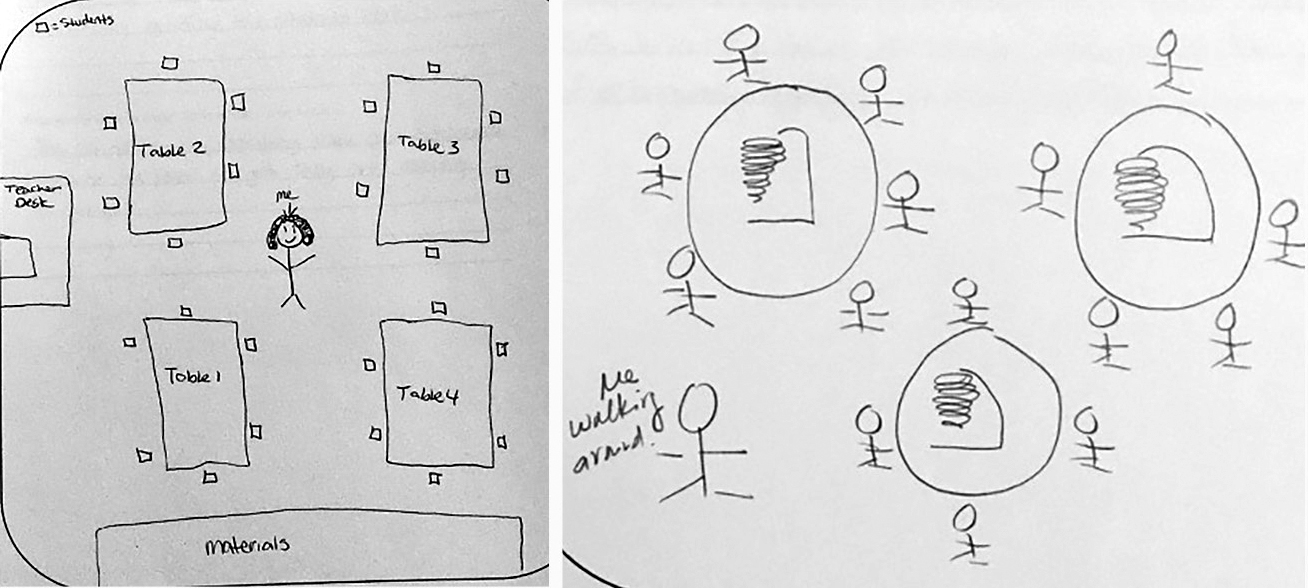

The PSTs with student-centered teaching beliefs considered the teacher as part of the students’ learning processes because they adopted a facilitator, guide, or scaffolder role rather than being the dominant figure who owns or provides the knowledge. One PST, for instance, used an orchestra conductor as a metaphor: “A teacher is like an orchestra conductor because he or she can only guide their works but not make the music for them.” The PSTs in this category viewed students as the main performers of the learning process. Consider the following metaphor from a participant PST: “A student is like a musician because his or her job is to perform well and they must practice and work hard to learn nuances of their instruments (their brains) and pieces (the subject).” The PSTs seemed to think teachers should guide or facilitate students’ learning because students are capable of taking responsibility in their own learning process (teacher as a guide): “A teacher is like the handlebars of a bike because they help guide and steer the directions of the lesson but are not the driving force, while a student is like wheels of a bike because they give the forward motion of the lesson.” In another example, one PST positioned students as the leaders (with teachers as facilitators): “A teacher is like a coach because they facilitate and counsel, but they should not do the task for students.” The teacher further added, “A student is like a great leader because they take charge of their own learning so that learning takes place.” The view of the teacher as a scaffolder emphasized indirect support given to students with the purpose of supporting students’ development as independent learners: “A student is like a garden because as you feed it, it grows and becomes bigger, stronger, and independent minded.” The PSTs’ views and drawings further supported their metaphors. For instance, several participants placed emphasis on discovery learning and one said, “We learn through discovering, not by being lectured.” The drawings constructed by the PSTs in this category indicated teachers walking around the classroom or standing next to students to help or guide them (see Figure 3).

Drawings indicating student-centered teaching approaches.

Note. In Figure 3A, the teacher walks around observing and indirectly guiding students’ work. The students are creating their own experiments and working in groups. In Figure 3B, the teacher walks around watching the students do the activities in groups. The teacher helps the students who are struggling by giving them ideas on how to expand their thoughts and do the activity. The students work on their projects, write about their investigations, and explain their thoughts to their peers.

In this study, another important finding was that 31.03% of the PSTs across all categories characterized student as a blank canvas, vacuum, or sponge ready to soak up all information that is either provided by teachers or learned through activities or experience. The following are representative examples of PSTs’ comments:

- A student is like a deep-sea sponge because they are ready to absorb whatever they feel is useful to their survival and existence.

- A student is like a sponge because they are ready and able to soak up any and all knowledge that surrounds them.

Conclusion

The NGSS are based on the constructivist philosophy, which posits that learning occurs if learners engage actively in the process of knowledge construction. The standards call for teachers to adapt their teaching beliefs to align their instructional practices with learner-centered approaches. However, consistent with the previous research (e.g., Buaraphan, 2011; Saban et al., 2007), this study illustrated that the PSTs perceived teaching science as knowledge transmission and the teacher as the only source and transmitter of knowledge. This study also demonstrated that even though the PSTs perceived that the teacher has control over the learning process, they possessed some aspects of constructivist perspectives. A considerable number of PSTs had mixed beliefs, which indicated that they considered teachers as the ones providing directed and structured inquiry “owning” the knowledge. However, this belief could be misleading and problematic because teachers may conceptualize their adopted views mainly as learner centered. In fact, most PSTs described the best way of science learning as the students’ engagement in science activities, though their drawings and metaphors revealed that they viewed students’ learning as still under the control of the more knowledgeable teacher, which could lead to less student involvement in the learning processes. The importance of structured or directed inquiry for science learning was emphasized by the previous standards (National Research Council, 2000); however, the ultimate goal is to prepare elementary students to gradually take the lead and engage in open inquiry in which they take responsibility for their own learning, which in turn helps them achieve intellectual independence. In that respect, teacher educators should place explicit emphasis on the features of open inquiry for science learning and the aspects of constructivist philosophy.

This study also showed that the PSTs assumed students were like sponges, always ready to acquire new knowledge, or that they were a blank canvas. Conversely, students entered the classroom with various prior conceptions, which often constituted a barrier to science learning (e.g., Driver & Erickson, 1983) or sometimes could be used as a foundation to build new knowledge (Clement et al., 1989). Opportunities should therefore be provided to preservice science teachers to help them understand the nature of learners’ prior conceptions.

Finally, based on this study, I recommend that educators offer opportunities for PSTs to critically reflect on and evaluate their teaching beliefs in light of the constructivist learning theory. Metaphor construction and drawing tasks could help educators identify and address PSTs’ tacit beliefs.

Preservice Science Education Teacher Preparation Teaching Strategies Postsecondary Pre-service Teachers