Middle School | Daily Do

Where Does Digestion Occur?

Biology Crosscutting Concepts Disciplinary Core Ideas Is Lesson Plan Life Science NGSS Phenomena Science and Engineering Practices Three-Dimensional Learning Middle School Grades 6-8

Introduction

In today's Daily Do, Where does digestion occur?, students engage in science and engineering practices and use patterns as a thinking tool to make sense of the phenomenon of digestion. Students will apply physical science ideas about chemical reactions and physical changes to develop life science ideas about digestion (the beginning of the science idea that the body is a system of multiple interacting subsystems). This task has been modified from its design to be used by middle school students, families, and teachers in distance learning. While students could complete this task independently, we encourage students to work virtually with peers or in the home with family members.

Before beginning the task, you may want to access the accompanying Where does digestion occur? Google slide presentation.

Daily Do Playlist: Digestive System

Where does digestion occur? is a stand-alone task. However, it can be taught as part of an instructional sequence in which students coherently build the science ideas that the body is a system of multiple interacting subsystems made up of organs specialized for particular body functions. In this third and final lesson in the playlist, students build on the science ideas introduced in the second lesson and answer the question they raised in the first lesson, "Why does some food disappear?"

What Have We Figured Out So Far? (Assessing Prior Knowledge)

In the Why does the cracker taste sweet? Daily Do, students figure out that digestion begins in the mouth. Use the following prompt to ensure students have ownership of this understanding, and show slide 2:

- What evidence did we use to support our claims that digestion begins in the mouth?

Listen for students to say the following:

- The amount of glucose increased because some types of complex carbohydrates were broken down.

- Saliva contains an enzyme called amylase that helps break down some types of complex carbohydrates into glucose.

- Chemical reactions occurred in the mouth.

At this point, we have not defined digestion. Show slide 3, and ask students this question:

- What does it mean when we say digestion?

Listen for students to respond as follows:

- When we break down food from larger particles into smaller particles

- When chemical reactions break down food into new substances

Work with students to define digestion as a chemical reaction that breaks down food. Have students record the definition on their Student Handouts. Give students a few minutes to answer question 1—Why do large food molecules, like certain carbohydrates, seem to disappear in the digestive system?—on their Student Handouts.

You may use this question as a formative assessment. Look for students to identify the following:

- As we chew our food, the tongue moves the food around in the mouth and mixes it with saliva.

- Saliva contains an enzyme, amylase, that breaks down certain complex carbohydrates into glucose.

- Glucose is small enough to be absorbed into the body.

What Phenomenon Are We Studying Today? (Introduce Phenomenon)

To transition to the next portion of the lesson—why we need to continue to investigate what happens to food in our bodies—use the following prompts:

- Do you think all of our food gets broken down in our mouths?

- Where do you think other food molecules, like proteins, get broken down?

- What could we do to figure it out?

Allow students to share their ideas. Accept all answers.

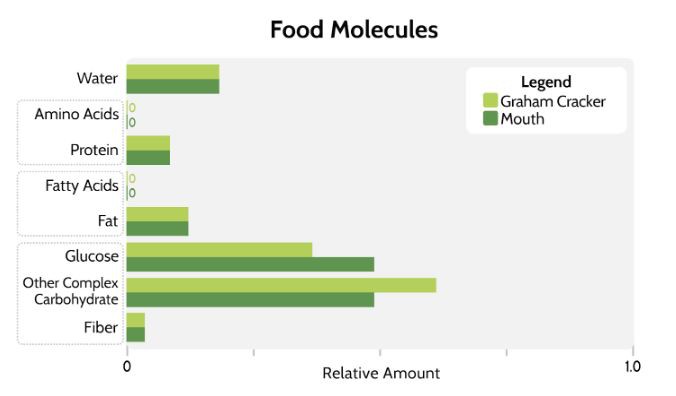

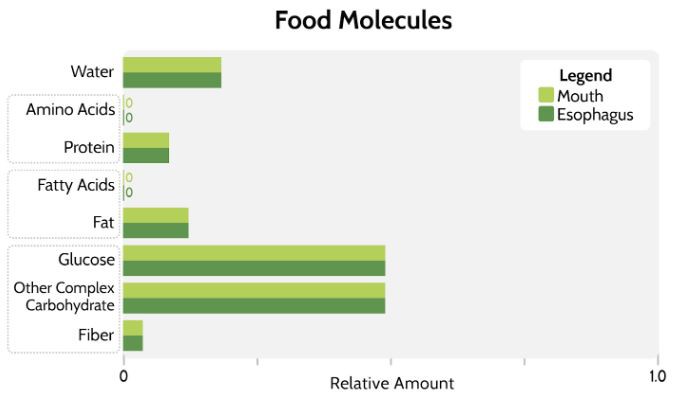

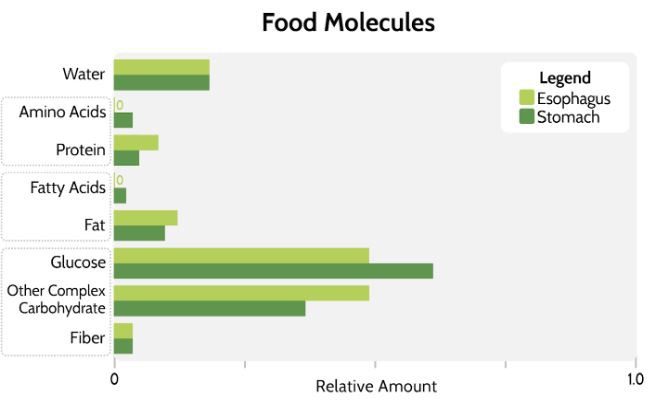

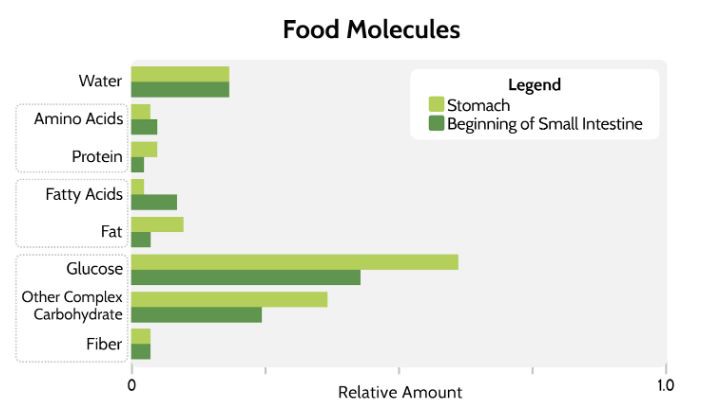

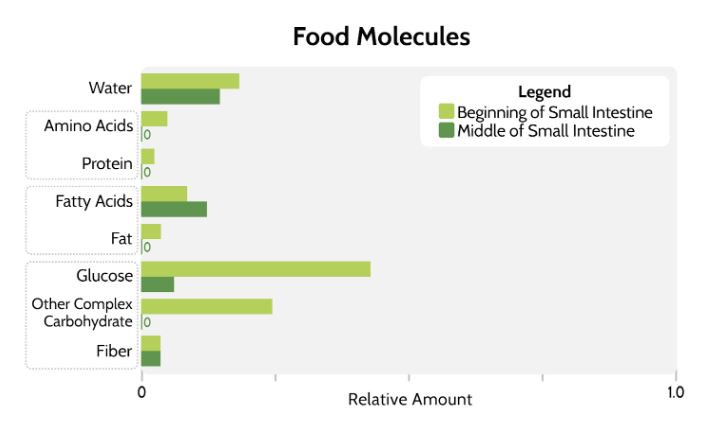

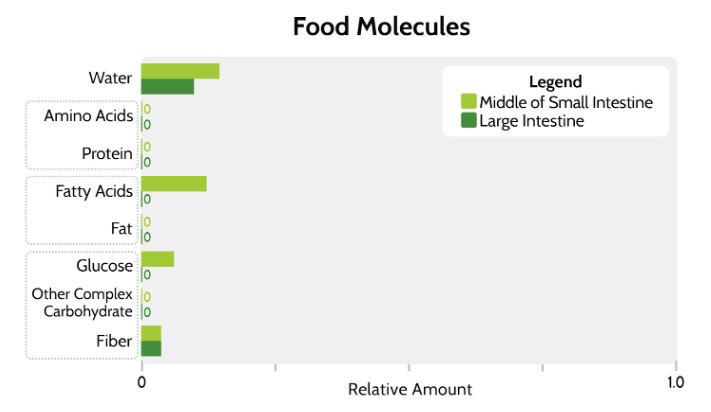

Remind students of what we have figured out about carbohydrates by saying, "Remember that we figured out that certain complex carbohydrates, like fiber, remained the same in the body, and other types of complex carbohydrates decreased in the mouth, while glucose increased. I have some graphs showing how other food molecules change during digestion from when before they enter a person's body through multiple organs in the digestive system." Show slide 4 to demonstrate to students how to analyze the data found in the Data Sheet.

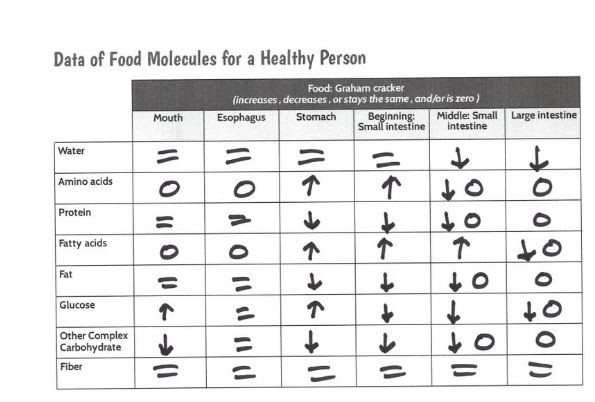

Have students work in groups to analyze the data found on the Data Sheet, and show the accompanying slides (slides 5–10). Tell students to record their data on question 2 in their Student Handouts.

What Does the Data Tell Us? (Building Consensus)

Ask students to share what they noticed in their data. Students will likely notice the following:

- Water remains the same until it reaches the middle of the small intestine and the large intestine, where it decreases.

- Amino acids do not appear until the stomach, then disappear in the middle of the small intestine.

- Protein levels remain constant until they decrease in the stomach and disappear in the middle of the small intestine.

- Fatty acids do not appear until the stomach, then disappear in the large intestine.

- Fat levels remain constant until they decrease in the stomach and disappear in the middle of the small intestine.

- Glucose increases in the mouth and stomach, then decreases throughout the small intestine and disappears in the large intestine.

- Other complex carbohydrates decrease in the mouth, stomach, and beginning of the small intestine. They disappear in the middle of the small intestine.

- Fiber does not change throughout the digestive system.

A sample completed chart appears below.

At this point, students may begin to identify patterns among certain types of food molecules, such as amino acids increase as proteins decrease. It is not critical to address these noticings until after the next step.

Remind students of the relationship among structures of carbohydrates that we figured out in the Daily Do Why does some food disappear? by saying, "Remember, we looked at the structure of carbohydrates and noticed that glucose molecules were smaller building blocks to larger molecules like other complex carbohydrates and fiber. I found similar data for other food molecules."

What Structures Do Other Food Molecules Have? (Digging Deeper)

Show slide 11, and give students time to examine the different molecular structures of food molecules found on their Student Handouts and answer question 3, What relationships among the different food molecules do you notice?

Allow students to share a relationship that they identify. Students should share the following:

- Amino acids are smaller pieces of proteins because they contain nitrogen and sulfur, while other food molecules do not contain either elements.

- Fatty acids can join together to create fat molecules; they both have similar shapes.

- Glucose molecules link together to form complex carbohydrates; they both have similar shapes.

Use the following prompt to help students make connections between the molecule images and their data tables (question 2).

- Think about the graham cracker moving through the different organs of the digestive system. How do the relationships among different food molecules help explain why the amount of one type of food molecule, like protein, might be decreasing by the same amount that a different food molecule, like amino acids, is increasing?

Look for students to identify the following:

- Larger food molecules, like proteins and fats, are getting broken down into smaller food molecules, like amino acids and fatty acids. The molecular structures show us that these smaller molecules are building blocks for larger molecules.

- When the larger food molecule is broken down into smaller pieces, the smaller food molecule's amount increases while the larger food molecule's amount decreases.

What Did We Figure Out? (Making Sense)

Lead a discussion to help students make sense of the data and images they have examined today using the following prompts:

- Which molecules only decrease over time and never increase?

- Which molecules increase and decrease?

- Do any types of molecules appear in the food at any point that weren't in it before it was eaten?

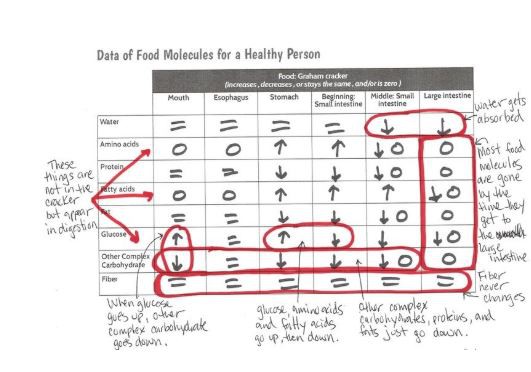

- Did anyone notice patterns in which one substance increased and another decreased in the same location?

Look for students to identify the following:

- Other complex carbohydrates, proteins, and fats only decrease.

- Glucose, fatty acids, and amino acids both increase and decrease.

- No amino acids or fatty acids were in the graham cracker until it reached the stomach.

- In the mouth and stomach, other complex carbohydrates decreased and glucose increased.

- In the stomach and beginning of the small intestine, amino acids increased and proteins decreased.

- In the stomach and the beginning of small intestine, fatty acids increased and fats decreased.

Tell students to add these noticings to their data tables (question 2) in their Student Handouts. A sample image appears below.

Where Does Digestion Occur? (Putting It All Together)

Ask students to develop claim, evidence, reasoning statements about the functions of each organ in the digestion system. Have them record their statements in question 4 of their Student Handouts.

Invite students to share their statements. Students should provide feedback on one another's claims by asking clarifying questions, comparing ideas, contrasting ideas, and giving critiques.

Students may identify claims such as these:

- Each organ in the digestive system has a different function.

- The stomach and small intestine work primarily to break down large food molecules.

- Small food molecules are mainly absorbed in the small intestine.

- The large intestine absorbs water.

- The esophagus does not play a role in breaking down food.

Use this statement as a formative assessment opportunity for the lesson. Students should identify pieces of evidence from the data to support their claims.