Middle School Elementary Informal Education | Daily Do

Why Are Plane Designs So Different?

Careers Crosscutting Concepts Disciplinary Core Ideas Engineering Is Lesson Plan NGSS Phenomena Physical Science Science and Engineering Practices Three-Dimensional Learning Middle School Elementary Informal Education Grade 3 Grades 6-8

Welcome to NSTA's Daily Do

Teachers and families across the country are facing a new reality of providing opportunities for students to do science through distance and home learning. The Daily Do is one of the ways NSTA is supporting teachers and families with this endeavor. Each weekday, NSTA will share a sensemaking task teachers and families can use to engage their students in authentic, relevant science learning. We encourage families to make time for family science learning (science is a social process!) and are dedicated to helping students and their families find balance between learning science and the day-to-day responsibilities they have to stay healthy and safe.

Interested in learning about other ways NSTA is supporting teachers and families? Visit the NSTA homepage.

Introduction

Structure and function is an important relationship in both science and engineering. Structures can be designed to serve particular functions by taking into account the properties of different materials. We can find structure-and-function relationships in both living and human-designed things at many scales.

In today's task, Why are plane designs so different?, students and their families engage in science and engineering practices and use the thinking tools of structure and function and patterns to figure out how the shapes of structures help determine a plane's function.

Let's Take Off!

Ask students, "Have you ever thought about why all planes aren't the same? There are two planes I'm thinking about in particular: an F-22 Raptor and a C5-B Galaxy."

Tell students you have a video of an F-22 Raptor that you want to share. Ask them to make observations and record them in their science notebook or on blank paper. You might give them time to make observations before starting the video.

Next, tell students you have a video of a USAF C-5 Galaxy up close takeoff at Abbotsford [Airport] to share (01:16 to end). Ask them to create a table titled Similarities and Differences Between an F-22 Raptor and a C-5B Galaxy; the table should have two columns, one labeled Similarities and the other labeled Differences. Ask students to note similarities and differences between the two planes as they watch the video.

Alternatively, ask students to make and record observations of the C-5B Galaxy as they watch the video. Then give them a few minutes to use their observations of the two planes to create the Similarities and Differences table.

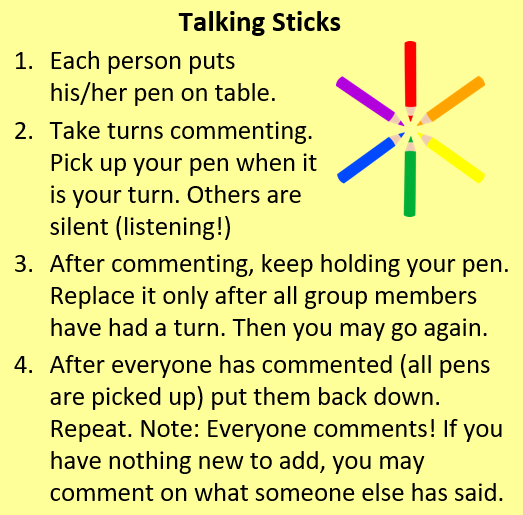

Assign students to small groups. Tell students they will use the Talking Stick protocol to make a claim about the function of one of the two planes (or both planes if students have two turns to share). Remind students to support their ideas with relevant evidence from their Similarities and Differences data.

Next, tell groups to choose one plane and be ready to share the following with the whole class:

- the group's claim about the function of the plane, and

- evidence that supports the claim.

Testing Two Airplane Designs

Tell students you have directions for paper airplanes that are similar to the F-22 Raptor and C5-B Galaxy.

Ask students, "What type of data should we collect to test our ideas about the functions of the two planes that we based on their structures?" Students might suggest the following:

- distance

- speed

- time in the air

- accuracy (ability to hit a target)

Set up testing stations around the room or outdoor area, if it's not too windy. Tell students that each group will be assigned data to collect (or you might allow groups to choose). Ideally, at least two groups will collect the same data. Ask the groups to plan their investigation and to identify how they will keep their testing fair. Then ask groups collecting the same type of data to meet to discuss their plan for investigation and fair-test list. Allow groups to make changes to their plans/lists based on feedback provided by another group.

Students' fair-test lists might include the following:

- Same student throws the planes/holds the plane the same.

- Same force is used to fly the plane.

- Distance is measured from starting point (tip of throwing student's foot, for example) to first point of contact with the ground.

- Planes are "uncrinkled" before each flight.

- Creases are the same on both planes (creased using the same method).

Ask students to create data tables including title and labels. This is a good opportunity to discuss the number of trials and the circumstances that might require students to "redo" a trial (e.g., airplane swooped away by wind; airplane strikes a student). You might consider asking students to include a space in their tables for observations if you plan to have students record the flights of their paper airplanes.

Now it's time to make the paper airplanes!

Materials (for each group)

- Letter-sized paper (8 1/2 in. x 11 in.), 2–4 sheets per group

- Stopwatch

- Meter stick or tape measure (you can also use steps to measure distance)

- Target

Note: You might choose to put materials at the stations instead of distributing them to groups.

Tell students that the directions for folding the paper airplanes are in the World War Squared video. You can play the video at slower speed: Settings > Playback Speed > 0.75 (or 0.5).

- 0:00–2:55 Hot Dog plane (includes brief introduction to National World War II Museum)

- 2:55–5:30 Hamburger plane

Ask students to check in with you (show you their paper airplanes) before they begin their investigations.

Allow student groups to conduct their investigations.

Analyzing Data: Forces of Flight

Assign students into groups based on their design goals (put students together who want improve the distance the plane travels, for example). Ask students to determine (1) the criteria for success for their designs and (2) how they will test their designs. Remind students to use the class data to help them determine success criteria and to refer to the fair-test list they generated when developing their testing procedure.

Give students an opportunity to individually brainstorm ideas for their design. As you walk around the room, ask questions like, "How do you think this structure (point to structure) will improve the function of distance/speed/accuracy/load? How will changing this structure affect the lift/drag/weight?"

Ask students to share their ideas with their group, then come to consensus on the group plan. Make sure each group has criteria for success, a testing procedure, and a complete design before allowing them to build their plane.

After students have created, tested, and improved their designs, bring the class back together. Ask each group to show their final design to the class and answer these questions (which include teacher notes):

- Was your design successful? How well does it meet the criteria for success?

- What is one thing you really like about your design? Even if the design was unsuccessful, students can identify a design feature that they like/are proud of that might become the basis of an improved design.

- How would you improve your design if you had more time or different materials? Engineers are always seeking to improve designs even when the design is successful.

You might ask students to share how the structures of their planes affected the lift, drag, and weight of their planes.

Note: Check out the How Can Properties Help Solve Problems? Daily Do for brainstorm, group plan, and reflection scaffolds.

The Engineering Design Process (EDP) comes in many forms. Engineers enter the EDP to create a new technology—or improve an existing one—to meet a need or want. Engineers on the job may start at any step, depending on the needs of a particular project.

To explore a real-world science and history connection, ask your students to read Catch a Glider (or read the story together).

You might ask students to discuss how the glider might have been improved to better rescue the stranded service members.

Explore STEM Careers in Aviation!

Tell students, "Now that you figured out the ways a plane's design affects its function, watch these videos to explore what it takes to enter exciting STEM careers in aviation!"

Aerospace Engineers—What Is It?

Consider a Career in Business Aviation

STEM Career Awareness is an important part of educating and preparing our students for the future workforce.

NSTA Collection of Resources for Today's Daily Do

NSTA has created a Why Are Plane Designs So Different? collection of resources to support teachers and families using this task. If you're an NSTA member, you can add this collection to your library by clicking Add to My Library, located near the top of the page (at right in the blue box).