Teaching STEM During a Pandemic

By Debra Shapiro

Whether they teach in an urban, rural, or suburban area, educators around the country who are teaching science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) remotely during the COVID-19 pandemic are saying the same thing: “We have students who are not doing any work.” Jan Barber-Doyle, a science teacher at Bell Gardens High School in Bell Gardens, California, sums up these teachers’ frustration: “Lack of student engagement is demoralizing.”

During remote learning, Barber-Doyle says it is difficult to reach students in her urban area because many “are not interested or are doing the minimum amount [of work to get by],…and there are no tools to manage this…Twenty percent don’t show up every day.” She adds, “My students are not taking on work without lots of questions and support from me…I have them for 38 minutes, so there’s no time.”

Some students “don’t know how to use the Chromebooks,” Barber-Doyle notes, “so I have to be the tech support as well.” And other technology issues have occurred that she can’t solve: “Student WiFi access is inconsistent. The school community experienced power outages due to rolling blackouts during high heat days, and I had to backpedal quite a bit on curriculum,” she reports.

“I am up until 10 p.m. learning the technology and planning…It feels like I’m a first-year teacher,” Barber-Doyle relates. “I need more humanity. This is why I got into teaching. I don’t want to be just a tech writer.” She says she gets some relief from isolation during meetings with her science department colleagues: “We have a meeting before the meeting to kid with [one another] and share personal stuff.”

Tom Traeger, who teaches physics at Monrovia High School in Monrovia, California, says some of his students “are not keeping up with asynchronous work because they are distracted by other stimuli or because they are taking care of younger siblings while their parents are at work. They don’t want to turn their cameras on because of what is going on in their world,” he explains. He says he has started giving a grade for participation while in synchronous learning and is “taking late work with no questions asked to help students get caught up.”

Traeger has been having better luck with his aviation and astronomy clubs, held during lunch. “I’ve been sending at-home activities to them. Students enjoy clubs because they can connect with others with like interests,” he observes.

Teaching Advanced Placement Physics has had its own challenges. The College Board “says students are responsible for all material that will be on the AP exam in May. I have had to cut a unit short to make sure I get to the other units,” Traeger reports.

“There’s been a setback to true implementation of the Next Generation Science Standards because students are having limited inquiry-based ‘aha’ moments. I can’t get materials out to them to do inquiry-based activities, and not all of them have materials at home,” Traeger laments. “Much of our funding has gone toward getting the technology, one-to-one Chromebooks.”

Looking ahead, Traeger observes, “I like to think we’ll come out stronger because of this. Teachers have had to learn new technology and have become better at it.”

Though his students are distance learning, Traeger is teaching from his school building. “I come to school to teach because my wife, also a high school science teacher, is teaching from home, and my kids are doing distance learning. There are just too many people in the house and not enough desk space for us to co-exist.”

Since his school went from in-person to remote learning, Kurtz Miller, a science teacher at Wayne High School in Huber Heights, Ohio, says he has been having student groups in Zoom or Google Meet breakout rooms conduct “hypothesis testing at home with materials they have available. Online simulations have their own challenges…and are okay for a supplement, but they don’t replace an authentic lab experience. Students can still do labs at home with scaffolding, support, and materials.”

In each lab group, “some will have the [basic materials]. For example, string and something to tie to it becomes a pendulum. A ball of some sort that can be dropped and a phone with a timer [enable students to do] a free-fall lab,” Miller explains, noting that “10% of the time, I have to deliver supplies to students, typically an item like a ruler or meter stick, for example.”

He gives students “two to four testable questions for each activity that aren’t too complicated and [for which] at least one student [in the breakout group] has the supplies.” Students “thrive during breakout time [because they’re] talking with other students instead of just the teacher,” he contends.

Miller points out that “there are all kind of free apps on [smartphones that can be used for] measurement and physics, such as PhysMo,” a video motion app. “The phone is a perfect lab; teachers just have to research the labs.” He has found articles on apps and testable questions in The Science Teacher, NSTA’s journal for high school teachers.

The groups require his support several times a week. “It’s definitely time consuming, and we can’t do as many labs, but they can be authentic,” Miller reports.

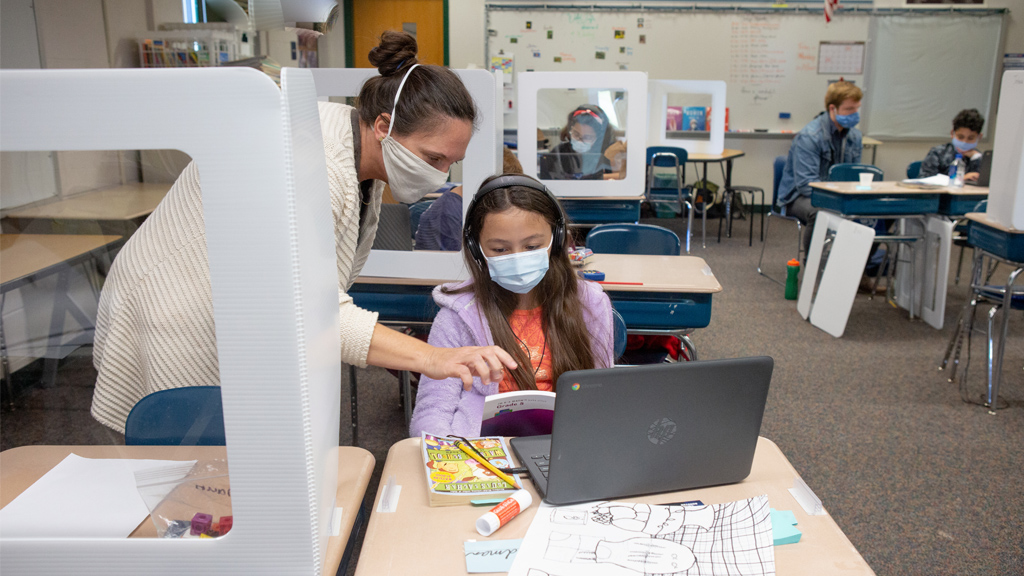

Some teachers are dealing with both remote and face-to-face classes. “We are in school full-time with simultaneous distance learners on camera in all classes,” says Anne Farley Schoeffler, middle school science teacher at Seton Catholic School in Hudson, Ohio. “My planning time is at least doubled as I struggle to adjust to this COVID situation [in which] students are not sharing supplies. I’ve switched some activities to demonstrations, some to individual activities with all the accompanying time to prepare, and some I’ve had to scrap and switch to online simulations or paper activities,” she explains.

“At the same time, I need to take into consideration the students working at home, who have not been getting as much attention…While I’m keeping the curriculum rich and interactive, I’m also well aware that students don’t have as much opportunity to work on some skills,” Schoeffler relates.

Schoeffler’s school is holding a STEM Fair this year, “but we’re calling it STEM Conference,” she notes. “I envision the adult panelists at a long table, and the students socially distanced in conference-style seating. Students learning at home will have a virtual judging panel. The rubric will be less open-ended and more targeted to the display boards and presentation skills. We want to give students a chance to practice public speaking as they talk about their projects,” she explains.

Schoeffler is somewhat optimistic about the future, noting that the pandemic “won’t be over soon, but it will be gone eventually…I look forward to resuming hands-on activities with shared materials. At the same time, the adjustments I’ve made will not go to waste as I am thinking carefully about almost everything I do, so I have also made upgrades and improvements.”

“Teaching in Title I schools is always a challenge, but [add] a pandemic, and teaching for many children stops,” asserts Sue Dembski, K–4 STEM educator at West Muskingum Elementary School in Zanesville, Ohio. “Our students did not have the technology necessary to access distance learning during the lockdown,” she explains, and in this rural area, some students’ homes “have no cell phone signal” or internet coverage. “So they missed months of essential education. It will take years, if ever, for them to catch up,” she maintains.

“While I did what I could to provide opportunities for STEM learning at home, because of the lack of technology and the lack of experience using the platforms, I had little participation,” even with putting her lessons on YouTube, Dembski reports. “It’s especially hard on the little ones...I wish public schools would take a lesson from the Montessori curriculum, [which has] less dependence on a child’s age and more on a child’s ability,” she contends.

Since school began in the fall, “our district has received federal funds to provide students that have chosen distance learning with computers and WiFi access. However, their education is primarily focused on basic learning. I am teaching in-person students, but because of the social distancing and the restrictions on sharing supplies, teaching STEM has been difficult. I have limited supplies to begin with and not enough for every child to have their own set of materials to complete challenges. I am trying to modify lessons to use supplies that children have already, but it is getting harder,” Dembski laments.

Dembski and her colleagues are trying to “do as much cross-curricular teaching as possible, getting kids to see those connections and make up for lost ground.” In addition, it’s important to “let students know that whatever they can do is okay. ‘You may be able to do it tomorrow [if you can’t today],’ I tell them. ‘We’ll get through this.’ Social and Emotional Learning is very important right now,” she observes.

“It is my hope that as time passes and more information is gained about the virus that education will be able to recover,” Dembski relates. “Many people say that distance learning is now a permanent part of education. I hope not, because nothing takes the place of learning with other children. If we want to encourage empathy, understanding, and cooperation, we must insist on in-person education for our children. The inequities will only get greater and will intensify.”

Christine Goonan, who teaches STEM in-person and remotely to second and third graders at Stony Hill School in Wilbraham, Massachusetts, says “hands-on and engineering design has been super limited. It’s not clear if we have funds for packages of materials for students.” She adds, “I used to do elaborate labs, but now I’m on a cart, with no classroom.”

Because students can’t share materials, “I’ve had to find things students can do by themselves, [such as working with] magnets…Students can’t learn from [one another]. Rich dialogue and conversation is where real learning happens…And their desk space is so small” that it also limits what they can do, Goonan points out.

Because teaching about friction is part of a state standard, “I was freaking out about how I would do a friction unit without having a fire,” Goonan confesses. Her solution was to have students rub wood, sandpaper, towels, and flannel and use a thermometer to show the difference in temperature when two things are rubbed (friction). “That was my ‘aha’ moment, figuring out an experiment with friction,” she relates.

The way students are having to learn during the pandemic “is temporary, but it shows the deficiencies of the system…Hands-on science with engineering is so important for students’ everyday lives, but we don’t have the investment needed in science. In a precipice of being the last country in science and math, we’ll be behind. There will be no Bill Gates, no Dr. Faucis…We need a national focus on science, like we had in the sixties [when President Kennedy] got the space program going,” she contends.

Pandemic PD

“I [attended more than] 33 webinars or web-based seminars in the 35 weeks we have been on distance learning. That sounds like a lot, but I think it speaks to a commitment by teachers to build skills for distance learning, and it is also a testament to the folks [who] recognize what it takes to be successful,” contends Barber-Doyle. She participated in four types of professional development (PD): “district-offered emergency training (at the end of last year), web-based digital tool training for delivering lessons online (screencasting, making videos, various extensions and apps), webinars from places that offer virtual field trips and have speakers bureaus, and content-specific seminars and webinars,” she relates.

“[M]ost of them had some value, but it is difficult to find sessions that are not targeting lower grades…Much of what I see now is a company selling a product or a modified rerun of something I have already tackled or have no interest in,” she laments. Most useful were “a three-day AVID DigitalXP workshop [in which I] learned how to use all sorts of digital tools for all sorts of reasons. The second was a series of webinars presented by SEI (Strategic Energy Innovations) that included energy auditing, renewable energy, climate change and air quality activities, and curriculum,” she recalls.

“I attended online professional development through Wright State University called the Jennings Educators Institute,” says Miller. (This three-day workshop “features networking, discussion, and a keynote speaker who is well-respected and well-known among educators in Ohio,” according to the website.) He also attended “a Dayton Regional STEM Center webinar on ‘What's Working’ with online instruction” and “GeoCAT [Geoscience Career Ambassador Training] seminars through a geology professor in Kansas.”

Miller admits that “[b]eing overloaded with adopting new technology, some of the topics did not interest me. During the professional development, I felt burned out due to the various stresses. This affected my ability to take in new information. Some of the professional development was related to ‘mindfulness’ and other strategies to reduce stress.”

Schoeffler attended a National Geographic class; a University of Colorado Boulder class related to the MOSAiC (Multidisciplinary Drifting Observatory for the Study of Arctic Climate) expedition; the Science Education Council of Ohio’s webinar series; the National Middle Level Science Teachers Association’s webinar series (she serves as the association’s president); and the NSTA Congress. “I feel I could go to more, but it’s not as engaging. I missed NSTA Boston so much,” she confesses. However, she found “some things I had access to that I [normally] wouldn’t because I don’t live close enough,” such as the Cleveland Museum of Natural History’s Professional Learning Community on ProjectCLE (Cleveland’s Living Environment), which involves environmental education PD once a month for 10 months.

Traeger attended the Southern California American Association of Physics Teachers conference and CK-12 Foundation sessions on Zoom. “They’ve been a wonderful help with physics resources,” he says, adding, “I’ve been attending more PD because I don’t have to travel, but I have Zoom burnout, so I’m turning some opportunities down.”

“Money was tight for me,” Goonan reports, “so I have had some free PD on racial equity, focusing on that…I’m looking forward to face-to-face PD with travel so I can bring the world to my students. I can’t wait!”

Engineering General Science News Physics Professional Learning old STEM Teaching Strategies Middle School Elementary High School