feature

Courageous Cheetah Car

Kindergarten engineers build a functional playground car with the help of family members

Science and Children—November/December 2022 (Volume 60, Issue 2)

By Rebecca Stobbs and Jeanne Norris

“I want to make a real-life car! Like one we can drive on the highway!” This comment came from a kindergartner during a conversation about engineering project work the students hoped to accomplish by the end of the year. As the rest of the class buzzed with excitement, a few students questioned the reality of that goal. “How can we build a real car? That seems dangerous! We need special tools!” After discussing it as a class, the initial student suggested, “How about a car for the playground?” That suggestion was met with more excitement by the students, and the Courageous Cheetahs’ Car Project was born!

Generating Student Interest

At the beginning of the year, our class decided our team name would be The Courageous Cheetahs. Students wanted to be brave and try new things in kindergarten. They encouraged one another not to give up when things get hard.

Our science curriculum begins by exploring different types of scientists and engineers and what skills they must have to do their jobs. The students learned that engineers have to think creatively to solve problems. They were excited about this connection to their own mission as The Courageous Cheetahs and wanted to study engineering as our project work focus for the year. The idea of “project work” stems from our school’s metaphor of School as Studio. At our school, we believe that students are capable citizens, and their ideas are to be recognized and celebrated by the teacher. We want students to feel ownership of their learning and even guide the learning that takes place in the classroom. We are a Reggio Emilia-inspired school, and learning through student-generated projects plays a big part in our school day.

To foster this project work, our class worked together to create a space in our classroom called the Creation Station where children could design and build projects out of many different materials, and they spent time both in our classroom and at home engineering different designs to solve problems. This is where most of our project work happened during the first semester of the school year.

In January, the class discussed what they would like to engineer before the school year ended. A few students suggested a real car, but other students realized that might not be possible because real cars can be dangerous. A student then said, “How about a car for the playground? One that we can drive on the playground!” All of the other students became excited about this idea, and we decided that was what we would do.

I knew this idea would require a lot of time and expertise, and I felt unprepared for a large building project. Students shared that their family members could build a doghouse, airplanes, and houses. They had tools and wood and could sew. They knew their family members could help make the car a reality.

Inviting Families

After hearing the students volunteer their family members for different jobs on this project, I sent out an email to the families, as well as a few personalized emails to family members who had careers that might benefit this project. I hoped family members would help students understand the challenges of taking a paper design and translating it into a functional playground car. One of the family members in our class was an architect, and when I reached out to her about this project, she agreed to help. She also volunteered her father, who was an experienced craftsman and a retired auto mechanic.

To avoid scheduling conflicts, I had to be flexible with our daily schedule so that family members were able to visit our class during their lunch breaks or outside of work hours. I also stayed after school to meet with family members to shop for supplies and work on the car design. Because of our school philosophy around project-based learning and family involvement, administrators in my school support teachers using time during the school day for such projects. We used our science block to do much of the work during the school day.

To encourage family engagement, I strive to create a welcoming atmosphere and sense of partnership from the first day of school. At the beginning of the year, I ask families to fill out a small survey in which I ask them to list any skills they would like to share with the class and if they would be willing to volunteer during the school day. Activities might include reading books, playing games, doing a job talk, or sharing a specific skill such as yoga or sewing. The students enjoy seeing their family members in their classroom, and the family members enjoy spending time with their children in another setting and meeting their classmates. Since the family members are always welcome to come help in our classroom, they were more than willing to help with this larger project, and they were as excited as students to see it come to completion.

Designing the Car

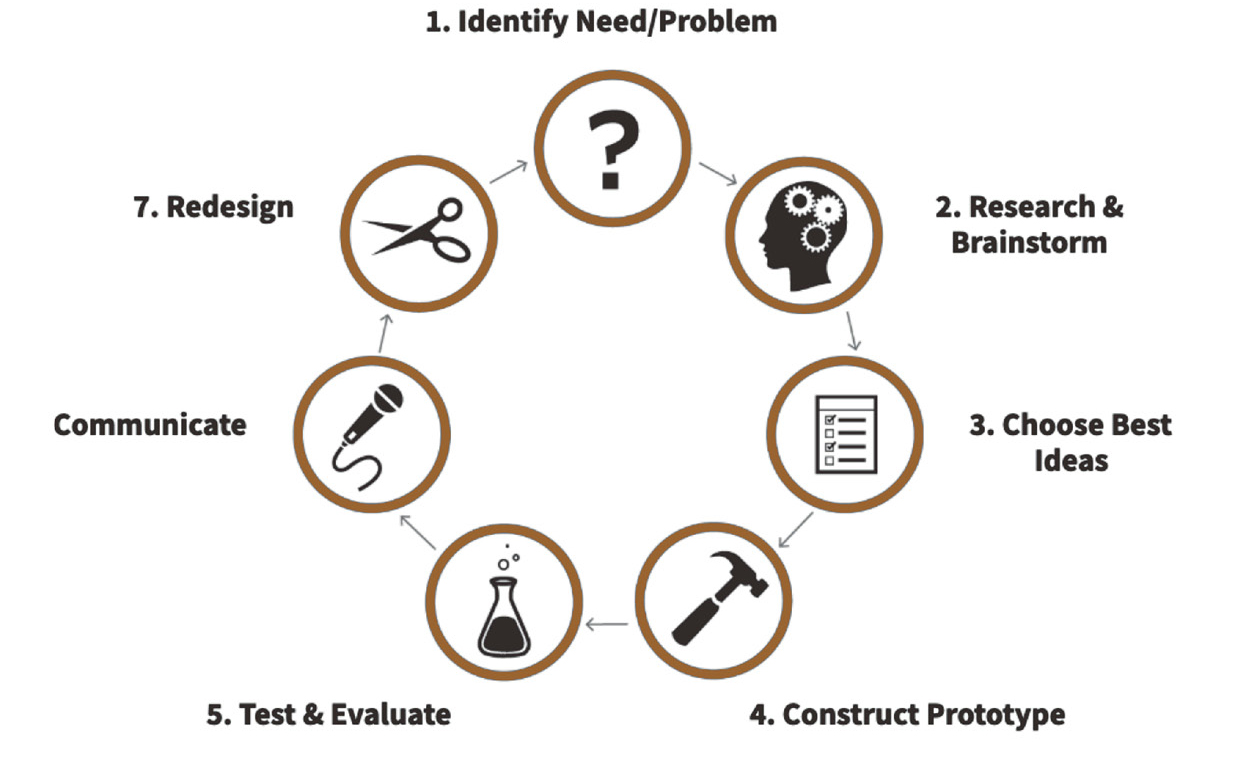

This project, from beginning to end, was guided by kindergartners. Once the students decided they wanted to build a car for the playground, I needed to create lessons to help them understand the engineering process required to build a car. Our science curriculum has a strong engineering focus, so students were already familiar with the engineering design cycle. I used a K–2 engineering design cycle poster, created by our local university partners, to have students follow along the steps in the process (Figure 1). In the previous quarter, the design challenge that accompanied our science unit on force and motion was to build a galimoto (a small toy that students can push or pull), so students were familiar with the engineering process to build a small car (such as creating a wheel and axle design that allows the tires to roll rather than slide). I needed to figure out how to push their thinking even further to design a larger, functional car.

Engineering design cycle.

Credit: mySci and the Institute for School Partnership

We began by looking at pictures of soapbox derby cars and other play cars online. From this research, students generated a list of criteria concerning how they wanted the car to look (structure) and how they wanted it to drive (function). I wanted students to use science concepts about force and motion that they had learned previously to engineer their car. I asked them questions about cause and effect and structure and function that would lead them to better designs. For example, I asked, “What would cause the car to move?” and “How can we design a structure in our car that would allow it to move forward?” We discussed the need for us to be able to make our car move. To do that, students would have to design a structure that allowed them to either push or pull the car. We discussed whether we wanted pedals or to use our feet on the ground to move it. As we tried to build a consensus, the class was split on this aspect of the car. In the end, we decided to forego the pedals due to time and material constraints.

Our Initial Paper Designs

The students then began to create designs on paper individually. It took several rounds of revisions. To scaffold for struggling students, I used exemplary student work samples to show the whole class and push their thinking for their own drawings. If students got stuck, I taught mini-lessons on certain topics. We had mini-lessons on drawing models, from being clear with our labels to “zooming in” to the parts of the car that are important to us, whether that was the steering wheel, a special horn, or fast tires. During these design sessions, I began to notice some students had some fanciful ideas for the car, such as an ejection seat or a device that would shoot fire out of the front of the car.

After noticing these creative ideas, I decided to teach a mini-lesson on realistic designs versus unrealistic designs. We read If I Built a Car by Chris Van Dusen (2005) and charted whether the designs in the book were realistic or unrealistic. After we read the book, I asked the students to design their cars again. This allowed me to assess whether they understood the need for realistic plans. We worked to develop a class consensus around which designs were most feasible given our material and time constraints. Through drawing revisions and consensus discussions, I assessed their understanding of the use of models to represent an object. I had to remind students that their models had to show how the parts of the car would serve a function, such as allowing the person in the car to push the car forward with their feet. Student drawings improved through these responsive teaching methods. They showed movement of the car by drawing arrows, illustrating the function of the structures they drew.

From 2-D Drawings to 3-D Small Models

The students spent a week on their drawings. They had time to draw many possible designs, and they had multiple chances to share their plans with others. During these sharing times, the students gave advice to one another to improve their plans. Each student then chose a favorite design and built a small model car based on the paper plans. They used craft sticks, thick cardstock, wheels from toy cars, skewer sticks, straws, and other upcycled materials. I asked family members to come in multiple times during our regular school hours to assist with this project, as the children worked to turn their 2-D plans into 3-D models. This was a great opportunity for us to discuss the importance of detailed drawings and how engineers have to take the materials they have available into consideration in their plans. The process was frustrating for some students, and many students had to change their plans completely to make a 3-D model car. We worked on managing our frustrations and thinking about how we were figuring out how to accomplish our big goal of building a real car.

To differentiate instruction for struggling or frustrated students, I paired children with family members who could support them and asked them guiding questions to make their models stronger. The support of special education teachers was invaluable during this time as well. One child with high needs was still able to build a model because of the one-on-one support. A colleague commented that she was so happy that the children with special needs were able to participate and play such a big role in the project.

Developing a Consensus

After the students built their models, I had them participate in a “gallery walk” where they walked around our classroom, and looked at all of the models, while noticing similarities and differences between the cars. Once the children had time to look at their classmates’ models, we discussed what many of the cars had in common. The children noted that all (or most) of the cars had four wheels, a place to sit, a steering wheel, headlights, a hole for our feet, and cheetah spots. The gallery walk and the discussions that came from it served to assess student understanding of the roles each structure played in the motion of the car. For example, I asked, “What is similar about your models? How can these parts of the car you modeled help us make a moving car?”

As students worked on their cars at school, I continued to communicate with the architect family member about building the real car. She asked for pictures of the students’ drawings and 3-D models, and I also gave her the list students created of what they hoped their car would have. She and her father came up with a final design for the car, using the designs and the wish list the students created.

She also came into our classroom with a blueprint of a house she had worked on in the past. She showed the students this blueprint and discussed the importance of including details in a plan. She also reiterated the idea that sometimes someone might have to give up an idea because it is not safe or functional. She told stories of past clients who wanted her to design a house that in reality would not be safe, and she told the class how she designed something similar to what they wanted while still designing a safe, functional house. The students had another discussion about what would be realistic to add to our car, and we connected what the family member shared to their own struggles coming up with safe, realistic plans.

The Build

After our lead family members came up with the design for a class car, we called a small group together to help get the pieces together for our build day. This group of five family members cut the wood we would need for our car into manageable pieces so we would not need to bring a saw. When we finally had our class build day on a Sunday in May on school grounds, 12 out of 20 students and their families joined us to put together the car. I knew I needed to host the build day when most family members weren’t working, and I let students know that even if they couldn’t be involved on that day, there would still be plenty for them to help with after the car was built. The family members helped the students glue, drill, and hammer the pieces together. Students were excited to use real tools while under instruction and supervision from their adults. Safety goggles with side guards, as well as gloves, must be used before, during, and after using or observing tools.

Once the car was built, the students decorated it like a cheetah, to honor our team name. This happened during the school day, in our classroom and in the art studio with help from the art teacher, so the students who were unable to attend the build day could be involved. We added a steering wheel (which I found at a hardware store in the play structure aisle) and headlights (inexpensive battery-operated push lights). Every student had a part to play in the design of this car, and they were so excited that their designs came to life in this car they could drive all around the playground!

Lasting Impacts

Students couldn’t wait to take the car to the playground and ride in it. They still come back to my classroom to check on the car. A new group of kindergartners is enjoying it now. This new class created a safety video to share with other kindergarten classes to let them know how to safely use the car, such as staying on the sidewalk while driving and sitting in the car rather than on top of the car.

Besides giving students a memory they hopefully will not forget, this project helped them have a deeper understanding of the engineering process. They had to work collaboratively to create the final product. Students lived through the frustrations of design revisions, teaching them to be persistent, flexible problem solvers. This project was a great opportunity to develop social-emotional skills we are just beginning to build in kindergarten.

This project inspired me to dream big with my class. When the students first suggested a car for the playground, I was intimidated, but my students and their families brought a wealth of knowledge. Family participation created a sense of ownership, community, and connection to science and engineering that will have a lasting effect on my students. All parents and other important adults in children’s lives have something to offer that will enrich the learning experience for all students.

Rebecca Stobbs (rebecca.stobbs@mrhschools.net) is a kindergarten teacher and K–6 science teacher leader at Maplewood Richmond Heights School District in Maplewood, Missouri. Jeanne Norris is a learning and partnership specialist at the University of Washington in Seattle.

Engineering Instructional Materials Interdisciplinary Grade K