Science for All

Digging Deeper Into Virtual Learning

How to Engage All Students in Science From a Distance

Science Scope—November/December 2020 (Volume 44, Issue 2)

By Kaitlyn McGlynn and Janey Kelly

Even if your school is not currently engaged in virtual instruction, it is likely that it will be necessary at some point during the school year. This month, therefore, we are focusing on the aspect of virtual learning that we and our colleagues struggled with most last spring: connecting with our hardest-to-reach learners.

Difficulties engaging students virtually

When the pandemic hit this past spring and schools closed, the most difficult part of our jobs was engaging those students who were the hardest to reach inside of the classroom. These included students who were often truant, struggling learners, English language learners, and those who had extensive social and emotional needs. Although this was certainly stressful and presented many challenges, the one benefit was that we knew our students well. We had had the majority of the school year to form relationships, which helped us understand how to meet our students’ needs when we went to full virtual instruction.

Unfortunately, this may not be the case in the current school year. How do you get students to engage if they only see you through a computer or tablet screen, or if they’ve only ever seen the top half of your face because the other half is behind a mask? Furthermore, how do we make sure that we are providing all of our students with equal access to our instruction, keeping in mind that fair isn’t always equal? Following are some suggestions.

Form meaningful partnerships

It’s important to make contact early on with your students’ families and to gather answers to several important questions (such as the ones below) to understand how to best support our students during periods of virtual instruction:

- Who lives with [student] at home?

- How many children in your home are of school age?

- Are the adults in your home working from home? Or going into work?

- Is there anyone available at home to assist [student] with school work? If yes, at what points during the day/evening is this person available to assist [student] with school work?

- Do you have access to technology? If so, what types of devices do you have access to during the day?

- Do you have access to the internet at home?

Although this isn’t an exhaustive list, it can be a helpful start for understanding what your students’ “working conditions” are like. It doesn’t matter if you send these surveys out via email in a Google form, by snail mail, or fill them out during an interview over the phone (which is our preferred option for our hardest-to-reach students). The answers to these questions will help you set realistic expectations for your students. For example, if you know that a student is the eldest of four children with parents/guardians both working outside of the home during the day, you should expect that this student’s day will largely be taken up with caring for younger siblings. It may be difficult for this student to find dedicated “work times” when he or she can focus entirely on school work during the day. Therefore, you and your colleagues can better coordinate your efforts to work with this student to define the appropriate “work times.” These times need to work for you, the student, and the family, as well as the (possible) guidance counselors and/or other support personnel. However, it is not necessary for an adult—whether that be a teacher, counselor, paraprofessional, or other personnel—to be logged on with the student to help with his or her school work during every minute of these defined “work times.” Students should absolutely be expected to follow through on completing some of their tasks independently, and then be held accountable if they don’t. To coordinate these work times, call on the help of your colleagues—whether that be co-teachers, learning support teachers, guidance counselors, or others—to help you make contact with the student to establish these work times. This past spring, Janey worked with her co-teacher to identify the students that needed help establishing a more defined schedule to complete their school tasks and then contacting them. As mentioned earlier, Janey often found the most success with contacting families via a phone call, but she didn’t stop at just working with her students to establish a new working schedule for them. After she and her student agreed on a new working schedule, Janey would then ask to speak to the student’s parent/guardian and make them aware of the new schedule and routine as well. Janey would also forward any schedule that she created with her students (such as the one in Figure 1) to the parents/guardians so that they were aware and could support their children at home accordingly.

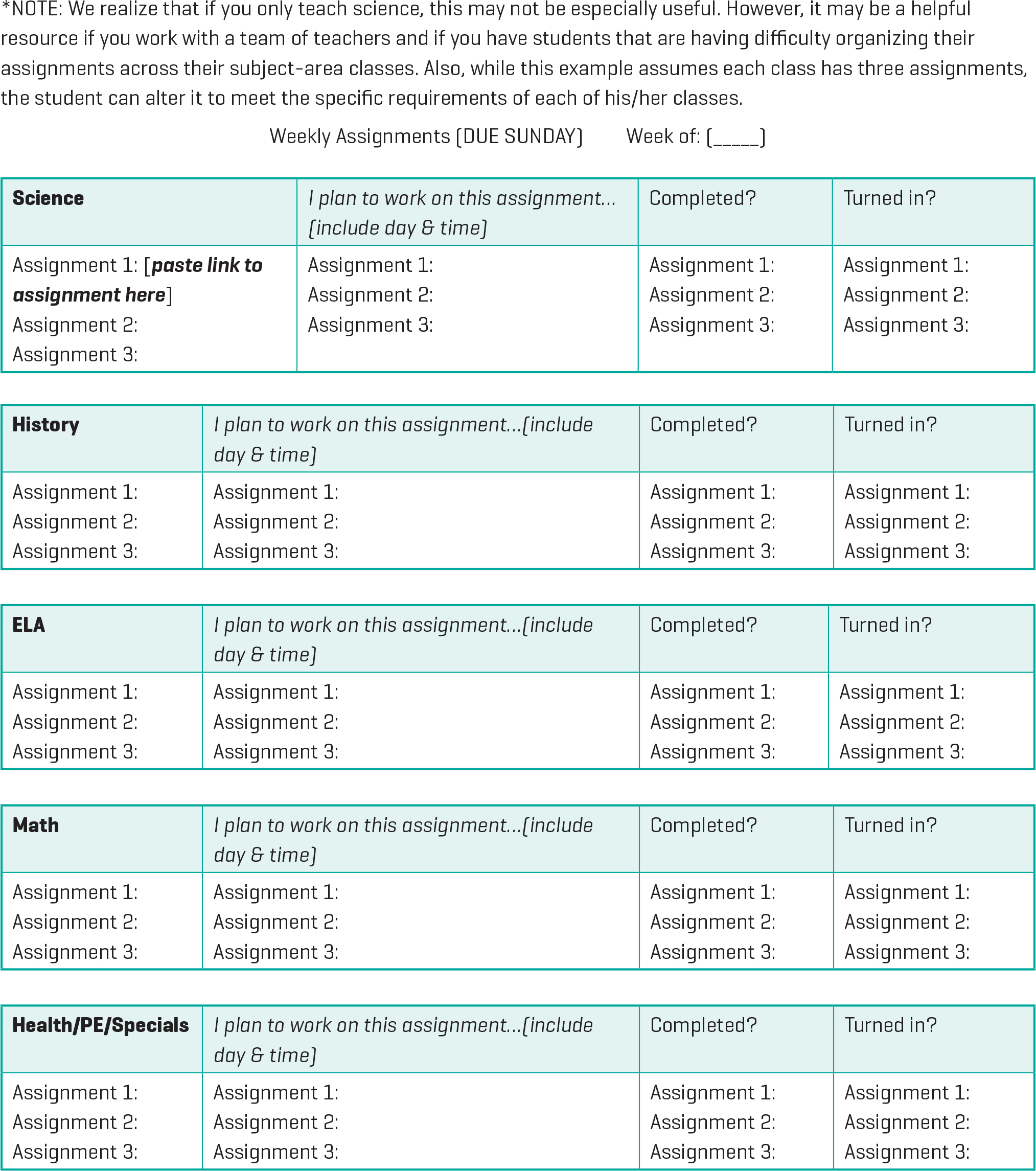

Virtual learning weekly assignment planner.

Make cohesive communication efforts

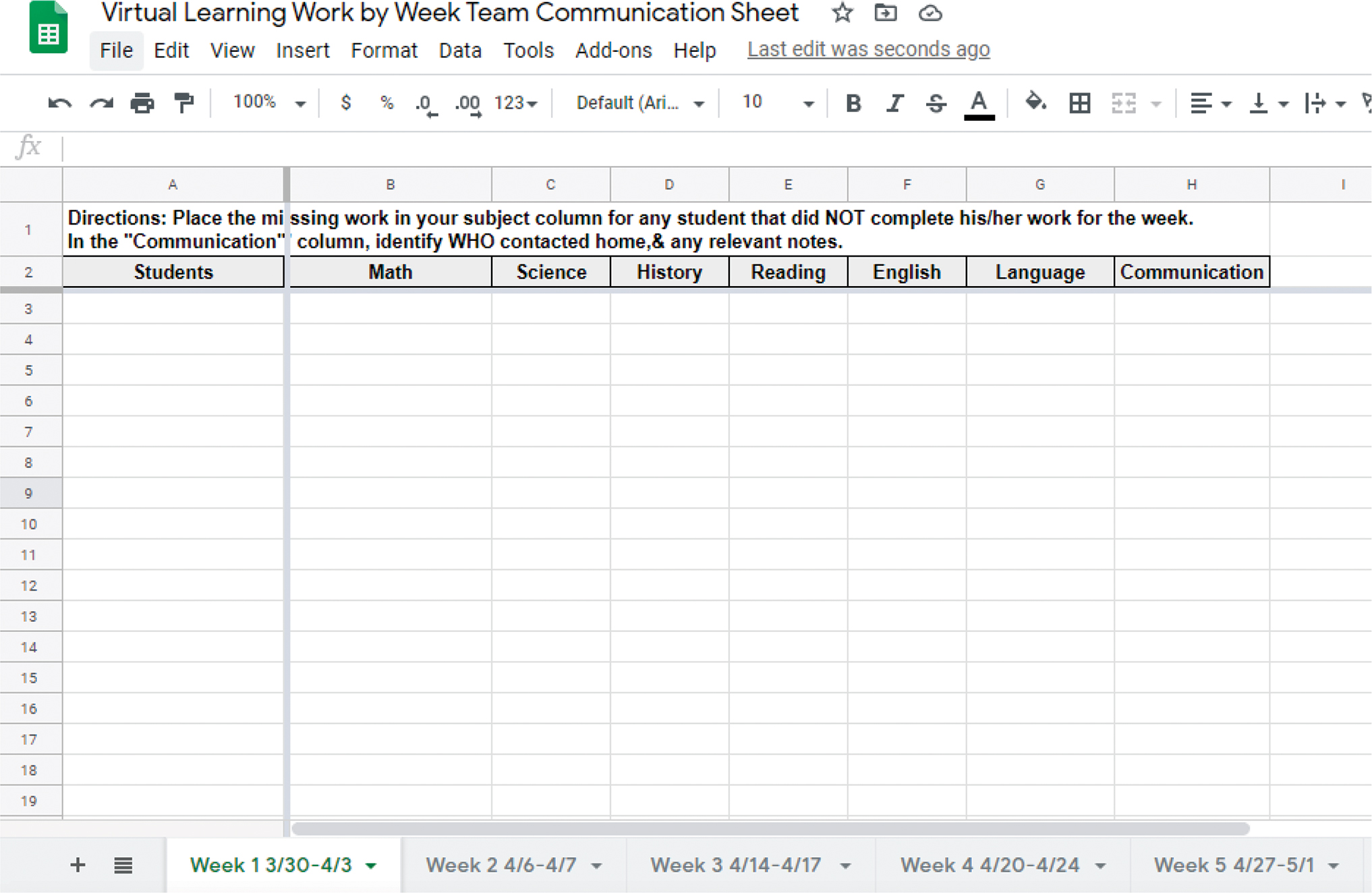

One of the biggest struggles that Janey and her colleagues faced this past spring was coordinating their efforts to communicate with parents/guardians. At first, most teachers were admirably taking the time to email and/or call the family of every child that had been missing work from the past week. However, this quickly began frustrating these families, because they were receiving two, three, four, and sometimes five of the same type of phone call at the beginning of every week to hear that their child did not complete their assigned work. To streamline their communication efforts, Janey’s team created a shared spreadsheet with all of their team students’ names and subject area classes (see Figure 2). They duplicated this sheet in a new tab for each week of virtual instruction. This sheet was also shared with learning support teachers, administrators, and other support personnel that worked with their students. Each week, Janey’s team agreed to update the sheet by Monday afternoon, simply by marking an “X” and perhaps writing a brief comment in their respective subject areas for any student that had failed to complete the previous week’s work. As the learning support teacher, Janey and her instructional assistant were the points of contact for the students on her caseload, while the rest of the team worked together to coordinate home communication for the remaining students. Not only did this prevent families from receiving multiple phone calls, it also lessened the workload for all teachers involved. As each student and family was contacted, Janey and her teammates would write a brief note in the last column on each sheet labeled “Communication” to document each communication attempt, as well as communicate any other necessary information to the rest of the team (i.e., when the student was expected to turn in the assignment, if there were unforeseen circumstances discussed with the family that had prevented the child from being able to complete their work the week before, etc.). Janey and her teammates also found that if they could keep the contact person from the team consistent, parents/guardians really appreciated it, which helped to solidify positive school–home relationships.

Shared communication sheet.

Establish consistent contact with students

When Kaitlyn and Janey reached out to families at the start of the school closure last spring, they found that many parents/guardians wanted to help their child but weren’t sure how, didn’t have the time to do so effectively, or both. One way that Kaitlyn and Janey helped remedy the situation was to set up weekly calls/video chats with the student. The parents/guardians were also welcome to be on the call if they were available (3P Learning 2020; Welcomer 2020). (Note: We recognize that your district may have different requirements with video chats, such as having a minimum number of participants log on, another teacher on the call with you, or requiring a parent/guardian to attend. Please follow your district’s requirements if you implement a weekly call with your students.)

Janey worked with her instructional assistant to contact their students by phone or by Zoom to assess which students wanted and/or needed support organizing and completing assignments. Once this was established, Janey and her instructional assistant spent Monday and Tuesday of each week contacting those students. During the calls, Janey would be online with her student and visit each of his or her Google Classrooms to find the links to the assignments the student was required to complete that week for each class. The links to these assignments were copied and pasted onto the graphic organizer included in Figure 1. Sometimes, in helping her students to find, copy, and paste the links to each of their assignments, Janey would also demonstrate how to use virtual simulations, labs, etc., that were assigned. This required Janey and her student to be on a Zoom call together so Janey could share her screen with the student to demonstrate how to navigate these virtual learning tools.

This graphic organizer made completing virtual assignments easier for those students who were having trouble navigating all of their virtual resources because they no longer had to go to two, three, or four different sites to find and complete the assignments for each class. They could just pull up their weekly graphic organizer and click the link to each assignment. The graphic organizer, therefore, helped her students organize everything they needed to complete weekly all in one spot. As another benefit, Janey could easily check their progress on completing such assignments by logging onto their graphic organizer because she was the owner of the document. If it looked like no progress was being made, Janey would check in with her colleagues to see if the student had completed the work and just hadn’t noted it on the their graphic organizer.

Twice a week, Janey also held office hours via Zoom so that her students could log in to ask for support with assignments. Janey advertised these office hours on both Google Classroom and in a weekly email to her students and parents/guardians. As time went on, participation increased, which was an encouraging sign that students were becoming more engaged with online learning.

Kaitlyn set a consistent time one day a week where students could log in for help to complete assignments from the week, catch up on missing assignments, or ask specific questions. The first week’s attendance was light, but she continued to post in Schoology (Schoology is the Learning Management System used by Kaitlyn’s school) about the meetings and reach out individually to students who needed it, as well as to their parents/guardians; attendance greatly improved as the weeks went on. Not only was Kaitlyn able to maximize her time by answering questions and assisting multiple students with the same assignment, but she was also able to touch base with students individually. She provided specific feedback on assignments and, more important, checked in with students in a socioemotional sense to make sure that they were coping with all the challenges the pandemic presented in a healthy way. When Kaitlyn had concerns about students, she discussed them with her school’s guidance counselor to ensure students got the appropriate help.

This brings us to our next point. As a science teacher with numerous students on your roster, you may not be either equipped or have the time to meaningfully connect with all of your students, especially those that are already typically disengaged. And sometimes, regardless of how much effort you put in, you just might not be able to reach them. If you are at a loss, try reaching out to your support personnel. Consider enlisting the help of guidance counselors, special education teachers, gifted support teachers, ESL teachers, reading/math specialists, therapists (speech, occupational, physical, etc.), and paraprofessionals. Because these staff members have worked with students in different settings or, in some cases, have known them prior to this school year, they may be helpful in getting a student to engage. These staff members also tend to have lower numbers of students (with the exception of guidance counselors), so they may have more time to spend with those students individually or in a small group. If you do employ the help of one of your colleagues, this doesn’t mean you’re off the hook. Continue to reach out to parents/guardians periodically, preferably by phone. We recommend having the student on the line as well, to ensure that everyone is on the same page. This helps build trust between you and the family, which increases the likelihood of students attending your class and completing assignments.

Design assessments purposefully

Each day during this past spring, Janey spent part of the day on the phone with some of her students. One thing she heard often was, “I’ll leave [subject area class] for last because that one is hard.” When Janey offered to work through the assignments in this class, she often found that her student wasn’t struggling so much with the material, but instead with how to access the material. She found that her students were more likely to give up if there were several websites or other places that they had to go to when completing their work. The lesson here? Stick to a familiar format for virtual learning assignments, and streamline them as much as possible.

Formatting the virtual learning environment

Janey and her co-teacher often heard from their students that they liked how the setup of the assignments was the same each week. They knew they’d get a Google Slide presentation at the beginning of each week with that week’s assignments on slide two, while all previous assignments were on the subsequent slides. Additionally, students always knew that they’d have exactly three graded assignments to complete. That never changed. What did change from week to week, however, were the assignments themselves (Mitchell 2020).

Streamline your assignments as much as possible

Janey and her co-teacher decided early on to include the links to all assignments, as well as any resources (such as links to articles, a PDF copy of the textbook, links to online simulations or videos, etc.) that students needed to complete the assignments directly on the weekly assignment slide mentioned above. The result? Students had everything they needed to complete their weekly assignments all in one place. Individual copies of worksheets or written work completed via Google Docs were also distributed to each student when the assignment was assigned in Google Classroom so students didn’t have to worry about remembering to attach their work to their assignment before turning it in. Janey and her co-teacher found that they had much higher levels of participation and completion of their assignments than their colleagues who had not adopted a similar structure. If you want to increase the participation of your struggling learners, decide on a structure you’re going to use for virtual learning, keep everything students need to complete the assignments in one spot, and then work to keep it all consistent (Mitchell 2020).

Weave “social time” into daily instruction

One of the major reasons the pandemic has been so challenging is that we have all been deprived of connections with those outside of our homes. It’s safe to say that no one is feeling this more than our middle school students. We suggest that you allot some of your synchronous time—perhaps the first five minutes—for social interaction. Not only will this time for socialization allow for connection between you and your students and your students and each other, but it will also make your class one that students want to attend each day. When students attend your class, it is more likely that they will complete your assignments. This is particularly true for our difficult-to-reach students. More than any other students, they need that social time, just like they do in school (3P Learning 2020; Cooper 2020; Welcomer 2020).

Bringing it all together

Teachers know that if and when distance learning occurs this year, it’s still going to be a challenge. This is especially true when considering our students who are often reluctant to participate in class, as going virtual makes it all the more difficult to reach them. Forming a personal connection with parents and students early is the first step. Collaborating with your colleagues and using support personnel to ensure consistent communication with families are also key factors, as is making your virtual learning format consistent and easy to follow. Finally, allowing time for students to connect in a nonacademic way with you and their classmates during synchronous learning might be the thing that keeps students logging on to your class each day. And that just might make all the difference in engaging all of your students.

Kaitlyn McGlynn (kaitlynjfetterman@gmail.com) and Janey Kelly (janeykoz14@gmail.com) are middle school special education teachers and certified reading specialists in the state of Pennsylvania, working in suburban Philadelphia in the Upper Merion Area School District and the Methacton School District, respectively. You can contact Kaitlyn and Janey at sci4allstudents@gmail.com with any questions you may have or suggestions for future columns.

Inclusion Instructional Materials Teacher Preparation Teaching Strategies