Feature

Building Teacher Professional Learning Infrastructure for Climate Justice Education

Connected Science Learning September-October 2021 (Volume 3, Issue 5)

By Meredith Lohr, Stacy Meyer, and Deb L. Morrison

A few hours into our first Climate Justice League session, one teacher paused to reflect that this professional learning experience was unlike anything she had participated in before. She described how she cared very deeply about justice issues and was accustomed to having these kinds of conversations with a small trusted group of friends over a glass of wine, but had never engaged in this kind of work in a professional setting. She was visibly energized by this observation, and it set the tone for our collaborative learning. —Reflections from a Climate Justice League Teacher Educator

While working with teachers in Washington State, we developed a set of principles for designing climate justice professional learning that aim to support teachers in urban, rural, and suburban schools to prepare students to understand and solve the systemic, interconnected challenges of climate justice. This article shares these principles and provides a vision of climate science teaching and learning that is educator centered, grounded in community, and motivated by action.

As the impacts of global climate change become harder to deny, educators across the world are recognizing the need to consider what climate change education should look like in K–12 schooling. At the same time, systemic racism and social injustice are significant concerns for many young people and teachers, although these topics are generally absent from science classrooms. While principles of climate literacy are well defined, the intersections of social justice with this field of learning are still emerging. Through collaborative efforts, we aim to create infrastructural support—systemic and coherent resources, professional learning experiences, and networking opportunities—for educators to weave this complex learning together and build their capacity to infuse climate justice teaching and learning into their classrooms (Bell 2019; Bowman et al. 2021).

The dynamic nature of climate justice teaching and learning poses challenges for educators and the educational systems that support them. Research indicates that knowledge of science, and specifically climate science, is not sufficient to create the social change needed to address the climate crisis (Dickinson et al. 2013). Instead, people need to feel personal connection to the issues, in ways that are framed by and resonate with communities (Lorenzoni et al. 2007; Wolf and Moser 2011; Wibeck 2014). To align with justice-centered teaching goals, science teaching must be asset-based, community-connected, and situated in issues salient for youth (Morales-Doyle 2017). Additionally, when learning about how climate change intersects with issues of social injustice, it is important to identify and challenge peoples’ implicit biases, avoid despair, and instill hope through action (Rodriguez and Morrison 2019; Stapleton 2019).

Relationships matter when learning about climate justice—relationality to place, to community, and to future (Cajete and Bear 2000; Love 2019). In professional learning settings, educators are often focused on the relationships they build with youth and families. To develop effective climate justice learning experiences, however, educators must also foster relationships with other educators, as well as with community organizations, and other justice-focused collaborators. To equip teachers to best support their students, professional learning about climate change should be strategically designed to build layers of relationality within communities. Our principles for designing climate justice professional learning help teachers provide relationship-based climate justice learning experiences for their students. Grounding students’ learning experiences in relevant relationships supports them to care about, understand, and help solve the interconnected challenges of climate justice.

ClimeTime

In Washington State, multiple organizations collaborate in a systemic, climate science learning initiative through a state-financed effort known as ClimeTime. The work began in 2017, when the state legislature passed a proviso for K–12 science education with an emphasis on climate science, which included $4 million in the first year and $3 million in subsequent years to support K–12 educator professional learning about climate change. ClimeTime fosters broad collaboration between state education agencies, community-based organizations, and the Institute of Science and Math Education at the University of Washington, which was engaged to guide the collaborative efforts of participating organizations. Several justice-oriented education projects have informed the work, including Learning In Places, the Climate Action Childhood Network, STEM Teaching Tools, and others. Over the last three years, thousands of teachers across Washington State have received professional development through ClimeTime, and the resources produced through the initiative are published as open educational resources (OER) and are freely accessible to all.

With funding and support from ClimeTime, our organizations collaborate to develop and implement effective professional development for teachers across the state. Key partners in this work include EarthGen, a nonprofit education organization focused on sustainability and environmental justice, and Educational Service District 112, a regional service agency that provides resources and support to 30 school districts in southwest Washington. Together we developed a professional development model for teachers, called STEM Seminars, which has been replicated across Washington State. In these collaborative workshops, we model NGSS teaching strategies and bring in climate scientists to share current data with teachers; our goal is to prepare teachers to engage students in standards-driven climate science learning with a focus on solutions.

In the 2018–19 school year, we recognized an upwelling of energy and excitement around issues of climate justice among participating teachers. In our workshop on the impact of climate change on human health, our partner Dr. Heidi Roop introduced educators to the Washington Environmental Health Disparities Map, an interactive mapping tool that illustrates how different environmental health factors are distributed across Washington. Teachers explored the map layers, investigated data from their own communities, and generated many questions. Their energetic conversations stimulated new ideas for connections to their existing curricula and inspired us to develop additional climate justice professional learning opportunities. At the same time, a number of current events in the world increased our sense of urgency around this work. We saw an explosion of youth activism with the School Strikes for Climate inspired by Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg. We also learned about the push for a climate justice resolution in Portland (Oregon) Public Schools as well as the powerful resources produced by Rethinking Schools and the Teach Climate Justice Campaign with the Zinn Education Project. While several existing programs explored climate justice through a social studies lens, our teachers needed support to make similar connections in the science classroom. When planning our climate science learning activities for the following year, we were determined to focus on climate justice.

Climate Justice League

In the fall of 2019, we launched our first cohort of the Climate Justice League (CJL). The intent of this project was to bring together middle school and high school science teachers to explore the intersection of climate change and social justice issues and learn how to integrate them into science instruction. Our first cohort had 14 teachers from diverse communities in southwest Washington, including large urban school districts, medium-sized suburban school districts, and small rural school districts. The cohort met for three full days over the course of the fall and winter to engage in shared learning around climate and environmental justice issues and inform their work with students. Our activities were designed to deepen teachers' own learning about climate justice with the goal of being adaptable for classroom use. Each teacher was asked to plan classroom learning activities that were appropriate for their own students and contexts. We also provided them with formative assessment tools to collect student feedback. In the Climate Justice League’s final session, teachers shared their experiences and discussed what they learned from implementing new activities with their students.

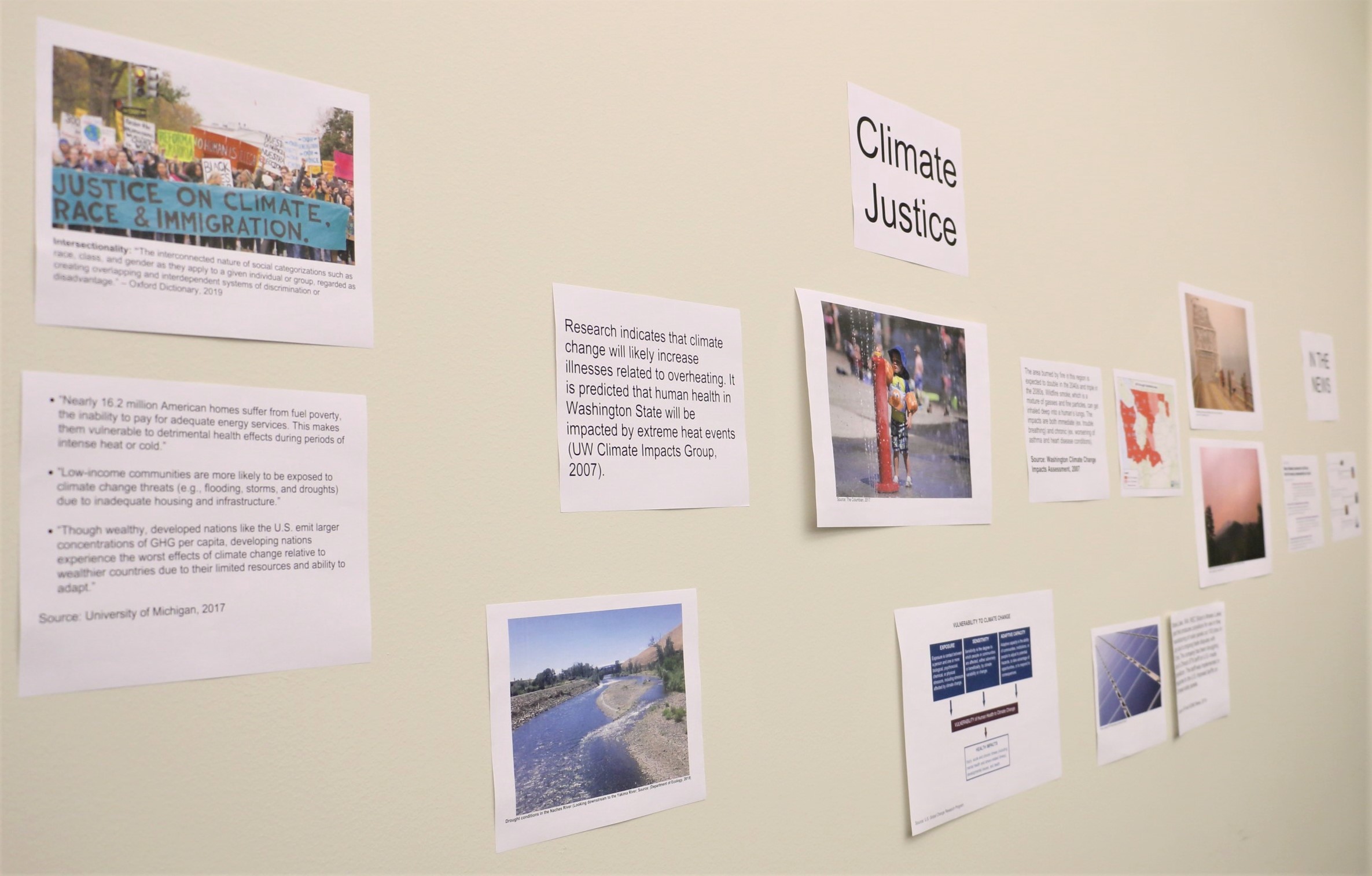

Throughout our sessions, teachers heard from guest presenters, including Tiffany Mendoza from Front and Centered, a frontline organization working at the intersection of racial equity and environmental justice; Tim Swinehart, a climate justice educator from Portland Public Schools; as well as partners from local higher education institutions. Our activities included a gallery walk, concept mapping, and analyzing local case studies. Educators explored resources from A People’s Curriculum for the Earth and Learning for Justice (formerly Teaching Tolerance). In our final session, each CJL teacher discussed activities they tried in their classrooms and presented some student work. In our culminating discussion, teachers were candid and supportive as they shared their experiences and reflections with each other.

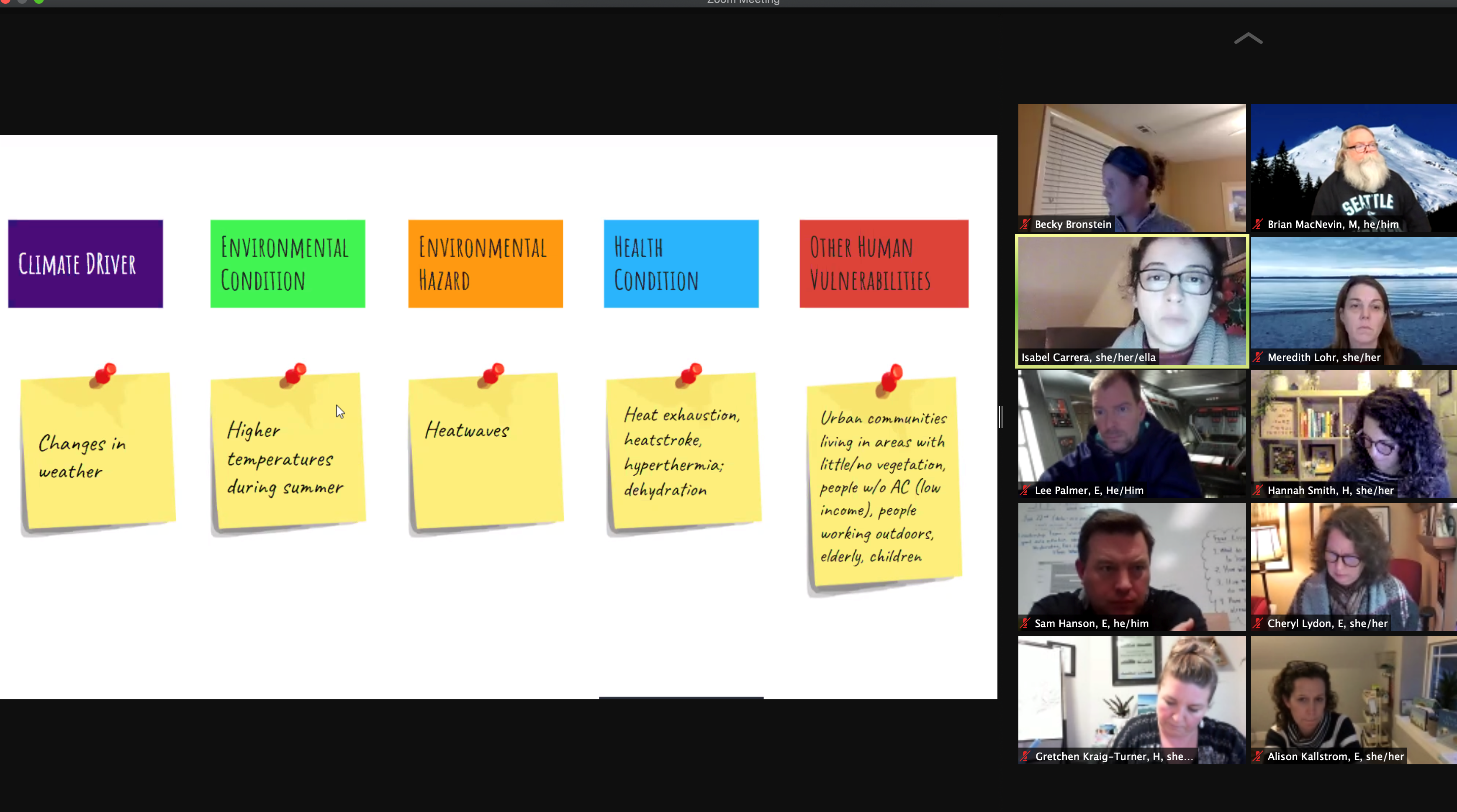

In the spring of 2020, protests over the killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery fueled teachers’ interest in bringing social justice into the classroom and inspired us to expand the Climate Justice League by simultaneously allowing continuation options for interested teachers and launching new first-year cohorts. Many of the teachers from our first cohort expressed interest in collaborating to develop new climate justice teaching resources for their classrooms. In response, we supported this group to come together to co-develop Climate Justice Storylines (Upadhyay and Han 2021) using the STEM Storyline model. At the same time, we also initiated two new cohorts of the CJL, including teachers from southwest Washington, the Puget Sound region, and northwest Washington. Because of the pandemic, these new cohorts convened online, participating in a sequence of synchronous and asynchronous learning activities over the course of several months. Informed by expert guest speakers, data, stories, and new perspectives, all three cohorts were charged with designing activities to engage their students in relevant climate justice learning.

Designing Justice-Focused Professional Learning

Developing and facilitating the Climate Justice League is a highly collaborative process, and we have sought to center the stories and perspectives of Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) in this work. As White educators in a White-dominated profession, we recognize that we must engage in climate justice education from a stance of justice, inquiry, curiosity, humility, and growth (Cochran-Smith 2010; Morales-Doyle 2017; Patterson and Gray 2019). In travelling our paths of individual and collective learning, a set of design principles has emerged that shape our thinking about how to approach climate justice education with teachers. With humility, we offer these observations in case they may be useful to others as they design and implement climate justice education initiatives within their own contexts. Our own thinking continues to evolve, and we are committed to expanding traditional boundaries and collaborating to improve our work.

Principle 1: Centering Teachers’ Expertise and Experience

Our first principle is a commitment to centering the experiences, perspectives, and expertise of teachers in their own professional learning. This idea is rooted in the ideas of community cultural wealth (Yosso 2005) and participatory design for educational justice (Bang and Vossoughi 2016). In each CJL cohort, we invite teachers to share their own stories and ideas with one another, which helps build a foundation of mutual trust. At the same time, we position ourselves (teacher educators and learning facilitators) as learning alongside teachers, acting with humility and a commitment to a growth mindset. By framing this as a shared journey, we also communicate our confidence in the expertise that teachers bring to this professional learning experience. This approach sets the stage for teachers to lean into one another for ideas and support, which we saw happen increasingly with our original CJL cohort over the course of two years. Working collectively, participating teachers continue to build on their learning and share their experience with other teachers across the state.

Honoring teacher experience and expertise also influences how we approach the development of learning resources for students. Rather than imposing our assumptions about what lesson plans to try, we rely on teachers to be the experts about their own students and communities. When teachers share how issues like forest fires and droughts impact their own students and their families, for example, we support them in developing related and relevant lessons. In our role as facilitators, we listen, reflect back what we are hearing, and offer resources and support when useful. In this way, teachers become the drivers of their own learning and resource development, relying on colleagues and facilitators to support their process. This approach also aligns with our view that the most effective way to engage in climate justice learning is to connect to issues that affect students and their communities.

Principle 2: Commitment to Sustained Relationships

Recognizing that climate justice learning can be emotionally challenging, we work to create supportive learning spaces for teachers to connect, push their own learning, and explore new ideas for their classrooms. Teachers in the CJL come from a diverse mix of schools and school districts across Washington, and many are meeting each other for the first time. As facilitators, we recognize that authentic engagement in equity and justice work requires trust, and we prioritize getting to know and understand our teacher partners and their local communities. Throughout the sessions, we build in ample time for teachers to work together in small groups to get to know one another and share about their students and communities. As a result, teachers report feeling less isolated because they know that there are others that support them. In fact, many teachers reflect that one of the most important benefits of the CJL has been meeting other teachers that share a similar passion for this work.

Teachers in the second year CJL cohort had already established strong and supportive relationships with one another, which allowed them to share openly about the challenges they are facing in their own schools and districts. From an unsupportive administrator, to parents criticizing justice-focused content, to community members attacking them because of their identity and/or political orientation, teachers engaged in climate justice education face real challenges. By turning to one another for affirmation, resources, and advice, teachers in the CJL help create an ecosystem of collective empowerment that sustains and propels their work.

Principle 3: Teacher Collective Empowerment

Not only do educators in the CJL gain support for infusing justice-focused teaching into their classrooms, they also begin to see themselves as agents of change in their communities. In the final meetings of each cohort, teachers' conversations shift to include recognizing injustices both inside and outside of the classroom. In the first CJL cohort, one teacher shared how she had been struggling with her district’s approach to tracking students in math and science, which she felt was misguided because it amplified existing inequities. Her conversations with other CJL teachers inspired her to vocalize her concerns and help her district explore other options that could better support all learners. Another teacher took on a leadership role in her local union, including presenting in front of the school board and leading equity work across the district. The support and solidarity developed among teachers in the cohorts motivates them to engage in civic action in their communities. For many teachers, the CJL is the only professional space in which they can have conversations about these issues; for them, this professional learning community is an essential source of rejuvenation and collective power.

Principle 4: Local Context and Partnerships

Grounding climate justice education in issues relevant to participating communities is another way to ensure that learning is personal and powerful for teachers and students. The CJL supports teachers to connect students with local issues and give them opportunities to design solutions and take action. For example, teachers from communities that have suffered the impacts of wildfire explore the causes of fires and the effects on their communities, and learn ways to build resiliency, especially among those who are disproportionately impacted.

To enrich teachers’ knowledge and perspective, we partner with and center the voices of diverse experts, including farmers, tribal leaders, youth activists, and scientists. In many circumstances, these partners co-create the agendas for professional learning sessions. The stories and information they share often inspire ideas for local topics that students could explore. For example, Dr. Megan Ybarra from the University of Washington presented her research and community organizing work on the Northwest Immigrant Detention Center in Tacoma, which sits on the traditional lands of the Puyallup tribe. Many teachers were not previously aware of the detention center or the related intersectional issues, which include being situated on a Superfund site and in close proximity to a proposed liquid natural gas facility. By bringing in experts to share their perspectives on climate justice in Washington’s communities, the CJL helps teachers understand local climate justice issues as well as their impacts on students and their families. This in turn helps teachers bring local climate justice issues to their own classrooms and contexts.

Principle 5: Sparking Action, Building Resilience

CJL is also committed to focusing on action and solutions. During the Climate Justice League, we regularly experience and witness a sense of grief and powerlessness in the face of these interconnected crises. In response, we build in time to attend to teachers’ social emotional needs and well-being. Knowing that young people struggle with these issues as well, we facilitate and model sense-making activities that can be used with students in the classroom.

Another way we combat the sense of despair is by highlighting solutions, positive change, and people working for justice, especially in our local communities. The story of Linda Garcia, a community leader who stopped an oil terminal from coming to her home of Vancouver, Washington, was inspiring to local teachers. Other examples of building local resilience include community-based food gardens, heat reduction strategies, and renewable energy projects. We support teachers to help their students design and implement their own solutions as well, and we encourage action projects that address authentic issues affecting their communities. As a result, students have led anti-idling campaigns, designed and installed community gardens, and initiated conversations with their families. (In communities where climate change and social justice are controversial issues, starting a conversation at home can be a powerful action!) Through CJL’s cohort model, teachers learn from one another’s projects and become inspired to be part of a network of collective action. Our goal is that both teachers and students develop a sense of agency to work for climate justice and understand that there are many ways to make a difference.

Implications

Through our work with the Climate Justice League, we are learning how to facilitate rich professional development that supports educators to engage in climate justice teaching and learning. By focusing on teachers’ experiences and local contexts, as well as building partnerships, our model promotes long-term capacity that is grounded in local communities. Moreover, our focus on action and resilience is not only good pedagogy when engaging young people in the face of despair, it also supports our own endurance as educators engaged in this work. Engaging in justice-focused pedagogy in this way centers the voices and expertise of BIPOC climate justice leaders in our programs, especially youth.

We offer these design principles, which have both guided and been further clarified through our work, as a framework for others to consider as they plan climate change education initiatives in their own diverse contexts. As fellow travelers along this journey, we welcome your feedback, suggestions, and ideas. If we are going to meet the challenge of preparing students for the challenges of climate injustice, we need to do it together.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Climate Justice League co-creators Sahar Arbab and Becky Bronstein. Thank you to guest speakers Tiffany Mendoza, Dr. Liza Finkel, Tim Swinehart, Dr. Isabel Carrera Zamanillo, Dr. Megan Ibarra, Terrell Engmann, Jordan Jackson, and Sanjana Bhajaj as well as our colleagues Pranjali Upadhyay and Rae Han for their contributions. We appreciate Dr. Ellen Ebert and the Washington State legislature for their leadership of the ClimeTime proviso, which made this work possible. Most importantly, we are grateful for the teachers in the Climate Justice League who inspire others through their courageous and innovative approach to teaching and learning.

Meredith Lohr is the Executive Director at EarthGen in Seattle, Washington. Stacy Meyer is a Regional Science Coordinator at Educational Service District 112 in Vancouver, Washington. Deb L. Morrison (http://www.debmorrison.me/) is a learning scientist with the Institute of Science + Math Education at the University of Washington in Seattle.

citation: Lohr, M., S. Meyer, and D.L. Morrison. 2021. Building teacher professional learning infrastructure for climate justice education. Connected Science Learning 3 (5). https://www.nsta.org/connected-science-learning/connected-science-learning-september-october-2021/building-teacher

Administration Climate Change Environmental Science Equity NGSS STEM Teacher Preparation Teaching Strategies Informal Education