Emerging Connections

Equity Strategies: Community Hosts and Design Thinking in a Middle School Summer Camp

There is a growing need to document, assess, and evaluate strategies used to successfully engage historically underserved youth in equitable Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (STEM) learning experiences (Penuel 2017). Equity strategies relate to ways that organizations leverage research and practice to promote “the agency of the educators and the learners, and they present opportunities for collective efforts to challenge historically shaped inequities that many engaged in everyday science seek to address” (Penuel 2017, p. 520). iINVENT attempts to enact and assess ongoing equity strategies to provide underrepresented youth (e.g., rural, low-income, Spanish speaking, first-generation college student) access to equitable STEM education experiences framed as invention. The specific strategies are (1) using Design Thinking, undergraduate mentors, and open-ended invention projects to support engagement in camp activities and (2) partnering with community hosts to find a location for the camp and recruit local youth.

What is iINVENT?

iINVENT is a free invention education mobile summer camp. Invention education refers to the “deliberate efforts to teach people how to approach problem finding and problem solving in ways that reflect the process and practices employed by accomplished inventors” (Couch, Flynn, and Skukauskaite 2019, p. 1). iINVENT is also a mobile summer camp, meaning that the camp (e.g., mentors and supplies) travels to the camp locations each week and returns to campus to resupply on weekends. Mentors travel throughout Oregon to sites selected by community hosts (one community per site). Once on-site, mentors connect with local community hosts, become familiar with available resources (location, facilities, etc.), interact with parents, and engage youth in a five-day invention summer camp. To host a camp, each community must find a suitable facility, provide lunch to campers at no cost, and recruit youth to participate.

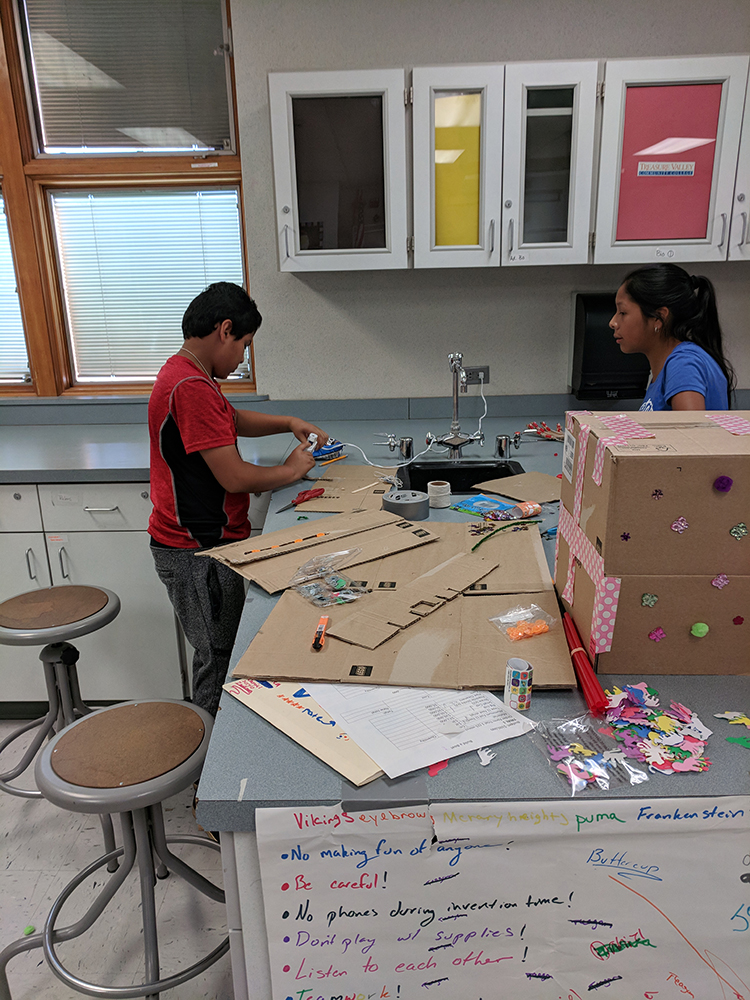

In iINVENT, youth draw upon their STEM knowledge and apply it to complete team-based open-ended invention projects guided by Design Thinking and mentored by college-age mentors. The iINVENT curriculum was developed at Oregon State University (OSU) Precollege Programs from previous activities, Stanford d.school’s Bootcamp bootleg (d.School 2019), and Oregon Mesa’s Invention ToolKit (Oregon Mesa 2018). iINVENT recruits OSU college students to lead camps as paid mentors. Mentors complete 24 hours of online training, take camp activities home to complete, select activities to lead during camp, and run a training camp with Precollege Programs modeling instruction. Once the mentors head out to the community, they facilitate activities, mentor teams, and act as “users” for youths’ invention projects. A user is someone who would benefit from an invention someone creates, and in camp the invention project relates to college life and the mentors’ personal experiences as college students.

Invention programs are typically designed to support youth engagement in STEM with an explicit focus on advancing innovation and entrepreneurship in the 21st century and improving youth confidence in their invention skills, STEM career awareness, and standardized math and science scores (Couch et al. 2019; Oregon Mesa 2018). At both the program (e.g., planning and youth recruitment) and instructional (e.g., theme, curriculum, and team-based invention project) levels, iINVENT attempts to use research-based equity strategies to engage the target population in invention education (Barton and Tan 2018; Montgomery 2001; National Research Council 2015).

Integrating Design Thinking

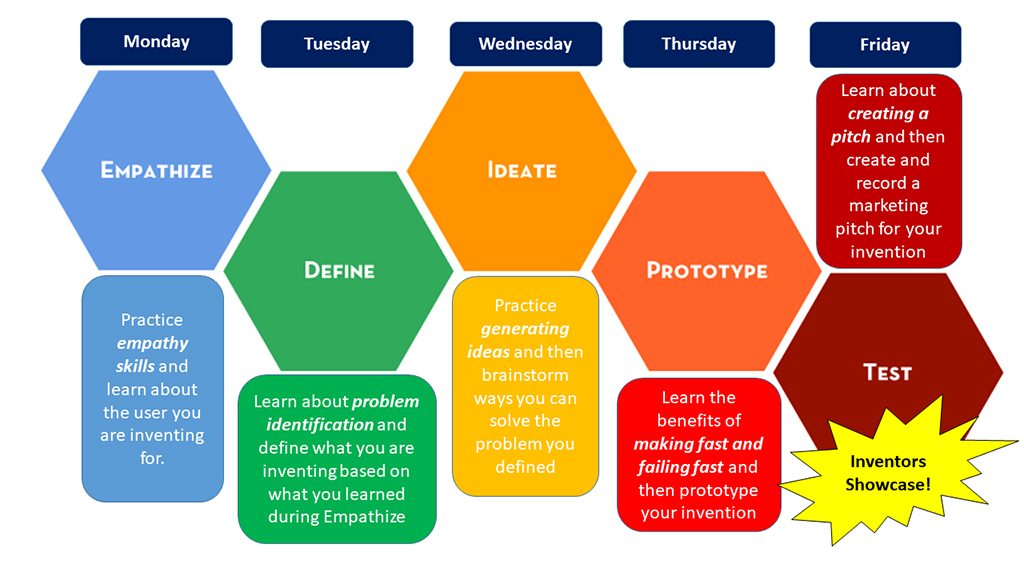

iINVENT uses a Design Thinking approach called Human-Centered Design (HCD). HCD is used to create daily themes to frame youth experiences as they apply STEM concepts to complete engineering design challenges and a collaborative invention project. OSU Precollege Programs used these resources to create HCD daily themes to frame camp activities and learning goals (see Figure 1; also see Appendix A in Supplemental Resources for camp outline and schedule).

The initial step in HCD is for the inventor, designer, or engineer, to “Empathize” with a user to better “Define” a problem from that user’s perspective. In the following steps of “Ideate” and “Prototype,” the inventor applies STEM concepts and practices to brainstorming solutions and creating a prototype for the user to provide feedback. The last step is “Test,” in which inventors evaluate how their invention could solve the users’ problems (and others like the users). The last day of camp ends with an “Inventors Showcase” where campers pitch their inventions to parents, guests, and fellow campers. The daily themes (Empathize, Define, Ideate, Prototype, and Test) help guide mentors' instruction of camp and call attention to the skills youth are learning. Research has shown that thematic instruction supports culturally responsive teaching practices, particularly with culturally and linguistically diverse youth (Barton and Tan 2018; Montgomery 2001). For example, on “Empathize” day a mentor could say, “Today is Empathy day; we will be focusing on empathizing by team-building and practicing interview skills to learn about each other. Later, we will interview the ‘users’ for our invention projects and learn about their needs.” The camp themes at iINVENT help guide youth in what they are doing and why they are doing it. The themes also frame how youth are expected to learn and how they can apply the theme to their invention projects.

The topic of iINVENT’s invention project is “challenges in college life.” This means that iINVENT’s college-age mentors also serve as the users of the solutions that campers design, which provides campers with access to these users throughout the camp and supports the HCD process. Mentors participate in a panel toward the beginning of camp to provide many examples of college life and problems they have (e.g., time management, connection with family back home, messy roommates, etc.). Youth then group into teams, select a topic to work on, and start their invention project guided by the HCD process. Youth spend at least 5–10 hours working on their invention project before they present on the last day of camp.

Community hosts as brokers

iINVENT success relies on hosts being able to navigate localized barriers to access and to recruit youth. To reduce barriers to participation and to recruit the target population, OSU Precollege Programs staff works with community hosts to “broker” iINVENT. Brokering refers to the ways that educational partners—such as organizations, educators (e.g., community hosts), and parents—help connect young people to learning opportunities (Barron 2014; Hand et al. 2013; Rogoff et al. 2016). iINVENT’s target audience is middle school youth from rural Oregon, particularly youth who are underrepresented in STEM professions and higher education. The host’s major responsibility is recruiting the targeted youth. Hosts are vital for recruiting because they are more likely to “understand the range of interests and preferences that [children in their community have], as well as their personal constraints in terms of time, transportation, and financial resources” (Barron 2014, p. 10) of particular youth, than OSU Precollege Programs staff. Hosts may also have an existing relationship with youth that they could leverage to recruit them to iINVENT.

To find hosts for iINVENT, OSU Precollege Programs contacted Oregon’s regional STEM Hubs, which help connect communities to learning materials, professionals, and educational opportunities. Part of their mission is to work “creatively in their region to build shared social and economic prosperity through STEM access, interest and attainment of skills, especially for students furthest from opportunity” (http://stemoregon.org/regional-stem-hubs/). To host a camp, hosts had to (1) express interest; (2) provide dates for a camp that matched summer availability; (3) have a space for youth and mentors with internet access, a projector, computer, and outdoor access; (4) recruit 20 youth; and (5) provide lunch.

Evaluating equity strategies

Evaluation of the iINVENT camp aimed to assess how effectively the following equity strategies supported achievement of camp outcomes: (1) using Design Thinking, undergraduate mentors, and open-ended invention projects to support engagement in camp activities, and

(2) partnering with community hosts to find a location for the camp and recruit youth. We evaluated program access, youth outcomes, and feedback from parents and the community hosts. The survey Measuring Engineering Design Self‐Efficacy by Carberry, Lee, and Ohland (2013) was developed for middle school youth and modified by OSU Precollege programs to reflect the language used in HCD (See Appendix B in Supplemental Resources). It was used in pre-post camp youth surveys. Youth completed questionnaires in person, while hosts and parents completed surveys online post-camp (See Appendix C in Supplemental Resources). The following sections will discuss the methods used to assess each strategy and related program outcomes. The concluding section discusses the affordances and constraints of the strategies and implications for future work.

Evaluation findings

Participants

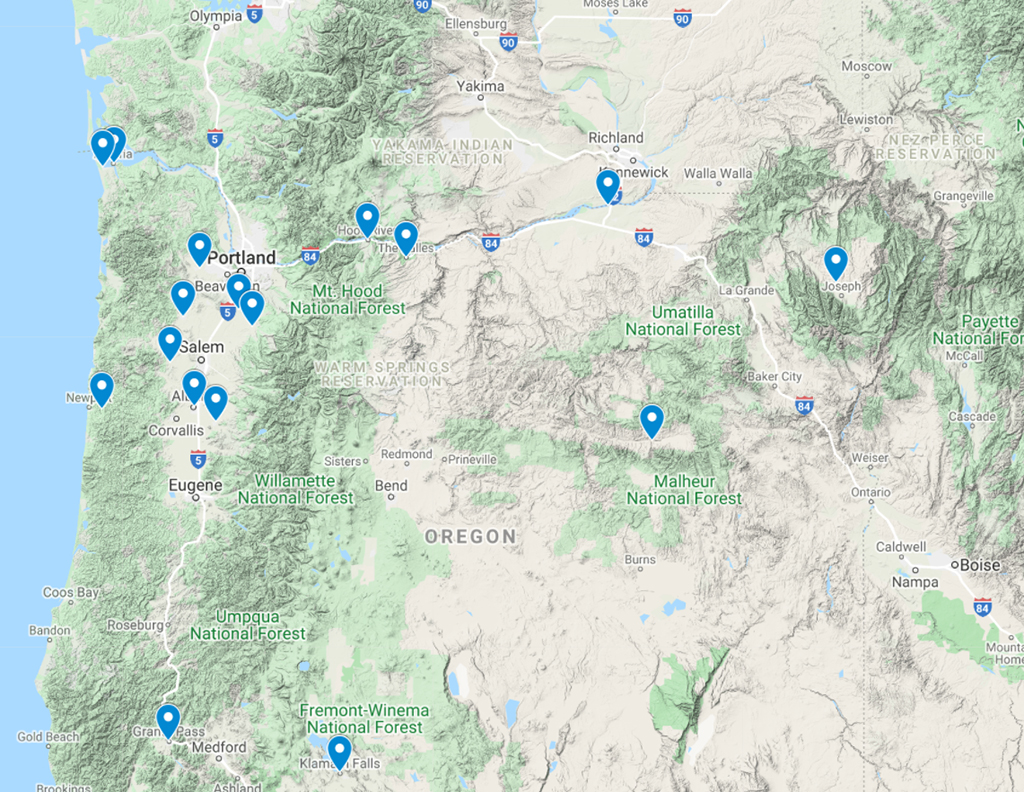

iINVENT drew on registration, participant demographic, and host survey data to assess the strategy of using community hosts to recruit the program's target population. iINVENT facilitated 19 mobile camps, in predominantly rural areas, at 18 locations in 2019 (see Figure 2).

The camps were located at 10 K–12 schools, four community centers, four community colleges, and one university. Four hundred and twenty-seven youth attended camps. Camp attendance ranged from 8 to 33 youth, and the average attendance was 22.

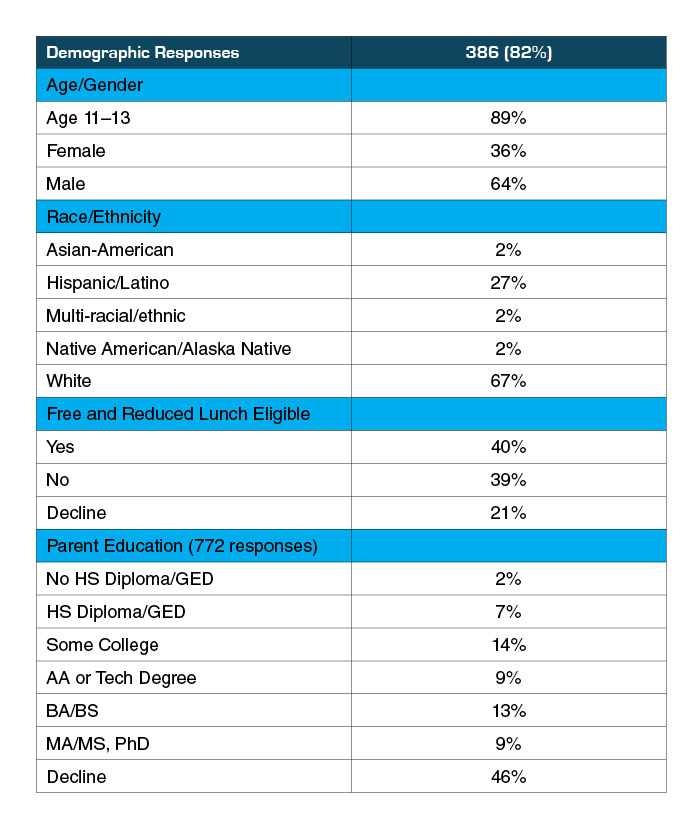

The program's target audience was underrepresented middle school youth from Oregon (e.g., rural, low-income, Spanish speaking, and/or first-generation college student). In 2019, 427 youth attended iINVENT, and 386 (82%) provided demographic information. The responses indicate participants were predominantly white (67%) and Hispanic/Latino (27%). Eighty-nine percent of the students were middle school age (11–13 years old). Sixty-four percent of the students identified as male, and 36% as female. Forty percent of the students identified as eligible for free and reduced lunch, while 21% declined to answer (See Table 1).

Design Thinking and program outcomes

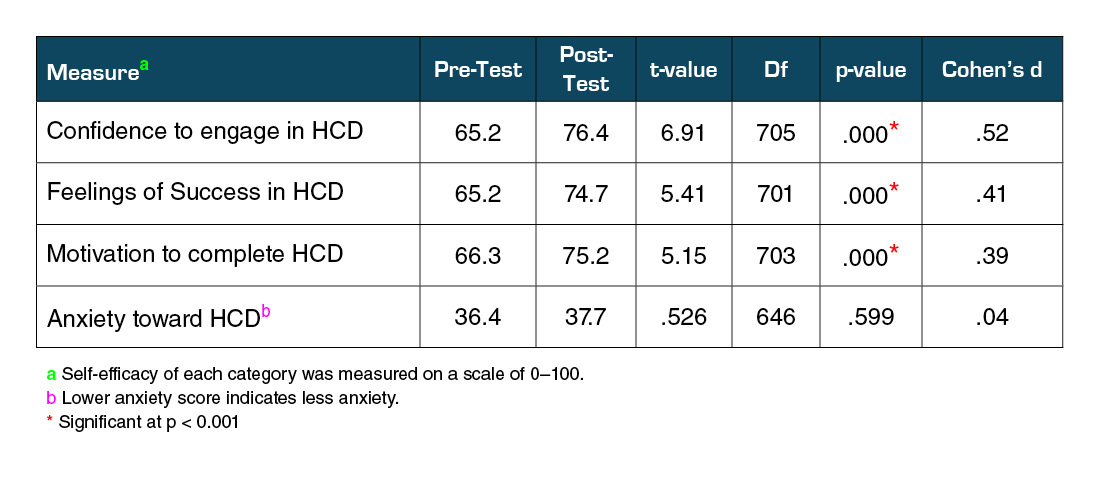

Before and after the camp, youth complete surveys to assess their self-efficacy related to HCD. Self-efficacy measures feelings of confidence, success, motivation, and reduced anxiety toward completing a task. The survey responses were analyzed using appropriate statistical measures to compare mean scores to capture gains in HCD Self-Efficacy (see Table 2).

Statistical analysis shows that youth participation significantly (p < .001) increased their confidence, feelings of success, and motivation toward HCD over the course of the camp. Additionally, the youth did not significantly gain anxiety toward HCD after completing the camp.

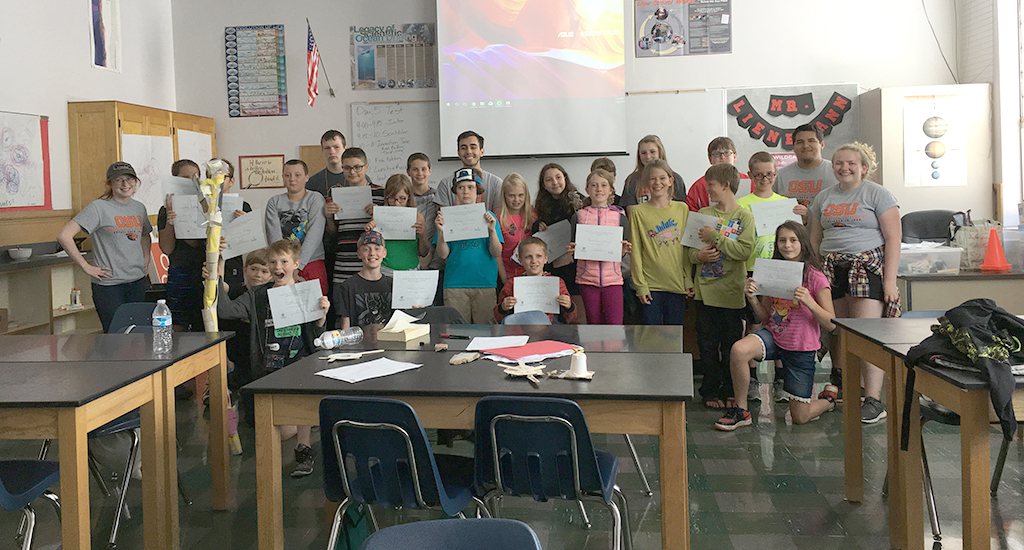

Youth also responded to short-answer questions that asked about their camp experience. The responses indicated participants gained the most out of working in invention teams, completing engineering activities, and the social relationships they formed at camp. One youth stated, “The invention group got me working better with others and gave me new friends, so I definitely got more from invention groups.” Campers also stated that learning about how their mentors got to college was important to them. One student said, “I really liked the talk about college. Sharing the things about college and how everybody could make it if they tried. It meant a lot, especially since there are a lot of anxieties about that.” These comments also provide insight into youth interactions with instructors and how the program provided youth opportunities to learn more about college life.

We also collected parent and host feedback on youth engagement. Seventy-two parents (18% response rate) completed the online survey (See Appendix C in Supplemental Resources). Parent responses describe youth enjoying camp and how their child benefited from the learning environment. One parent stated that her “…boys had so much fun. They struggle with their learning environment at the school they attend. But they loved the camp so much. They have not stopped talking about it or all the things they have been learning.” Another parent also commented on the camp environment and attributed their child’s benefits to the mentors:

“This opportunity made a huge impact on my child. She was excited to share her experience without being prompted; it really showed she was pleased with what they were doing.”

Another parent summarized their child’s experience as “it was great to see all the fun stuff they did [at the Inventors Showcase] and to hear all about the [mentors] from my daughter, she knew all their majors and I could tell she really enjoyed meeting them.” These parent quotes reinforce the positive experience youth had and help give context to the gains in HCD self-efficacy.

Similar to the parent survey, hosts provided feedback on iINVENT mentors’ interaction with youth. Several hosts commented on the mentors’ ability to create a positive learning environment, one stated:

“This crew of counselors were very effective with the kids! They were a well-balanced team in terms of temperament. They set a positive tone and clear expectations from the beginning. They engaged positively, in all of the activities. They were flexible with the kids, i.e., some wanting more quiet free time, others wanting more active free time.”

Hosts also comment on how camper engagement increased over the week. They saw youth initially hesitant to participate in the program but becoming engaged over time:

“Some kids make it clear to their parents that they did not want to stay and participate in the camp. I told the students, give it a full day, if after today you don't want to stay, you don't have to. … On Friday, the last day of camp, I saw the student again, all flustered from having fun. When I approached him and asked if he had enjoyed the camp and whether he would sign up next year, he smiled and said yes. This was the same for quite a few kids.”

Youth, parents, and community hosts reported campers as enthusiastically engaged in iINVENT. They also said the healthy connections youth made with the instructors bolstered significant student gains in HCD self-efficacy.

Community hosts and access

In the post-camp survey, hosts were asked about why they hosted a camp, how much time they spent planning, and the most straightforward and the most difficult parts of fulfilling their obligation as a camp host (see Appendix C in Supplemental Resources). Thirteen of eighteen hosts completed the post-camp survey (78% response rate). When asked why they chose to host a camp, responses included:

- 85% to help youth learn about STEM

- 77% to provide access to learning experiences for youth

- 62% to help youth learn about college

- 54% to provide youth with a safe place during summer

One host from a community college described why they hosted iINVENT:

“There are not very many options for teenage students in [my community] for students to be active in the summer and I love to host this camp [in my community]. I think it's a wonderful, educational, and fun camp for students to learn about STEM and hopefully be inspired to pursue a career in STEM.”

Hosts report taking between 5 and over 20 hours to plan a camp. Hosts further elaborated on the ease of planning by rating how easy/difficult it was for them to provide the space, recruit youth, provide lunch, have personnel on-site, and find transportation for youth. Hosts used a scale of “Extremely easy,” “Somewhat easy,” “Neither easy nor difficult,” “Somewhat difficult,” and “Extremely Difficult,” to rate each task (see Figure 3).

![Ease and difficulty of hosting iINVENT.]](/sites/default/files/2020-09/Talamantes_Figure3_edit.jpg)

Figure 3 shows the ease and difficulty of the tasks that OSU Precollege programs asked hosts to accomplish to host an iINVENT camp. The analysis shows that, in order, finding a location for the camp, providing lunch for youth, and having a community host (or other personnel) on-site were less difficult for some hosts to accomplish when compared to recruiting youth and finding transportation. Hosts further explained the challenge of recruiting youth as:

“Our biggest problem was that we have such a limited number of youth. The same week we offered the iINVENT camp, we had the following camps for youth of the same age group: Christian summer camp, 4-H outdoor camp, Vacation Bible School, Regional playoffs for both softball and little league… As you can see, our kids were spread out over a wide variety of camps/activities.”

This host raises the issue that there are a finite number of middle school–age youth in their community and that other programs can provide competition. Another host also explained more about the challenges of reaching the program’s target population:

“The most difficult piece for me is recruiting the kids. This is in large part because I seek to target my recruitment to make sure to include as many kids of color and also kids without the means to attend other camps due to cost, as I can. The camp is open to all but I really do try to get the word out to a diverse audience.”

Another host expanded on the sentiment of providing access to underserved youth and commented on the need for Spanish-speaking OSU Precollege programs staff and mentors:

“This camp is an excellent opportunity to connect with underserved communities. Having a Spanish-speaking counselor could help with connecting with families. If this is not possible, I would say that it is crucial to have a Spanish-speaker available at your campus office, to make those contacts with families prior to the start of camp.”

Host responses show that one of the main challenges to having a successful summer camp is youth recruitment. Findings regarding youth recruitment indicate that it is helpful to have shared responsibility between iINVENT and camp hosts to reach the target population.

Internal program data also revealed that hosts frequently placed camps at the same site as other social services, such as USDA lunch programs, summer school, busing, and other youth-serving organizations (e.g., Boys and Girls Clubs and Juntos). This resource connection shows another benefit to relying on local hosts because they may have access to local resources. While camp hosts were required to provide lunch at no cost to the participants, they rated providing food as the second most straightforward task, behind securing a space.

Conclusion

Using Design Thinking to frame invention education. Design Thinking and invention put students at the center of problem-finding and problem-solving processes (Barton and Tan 2018; Carroll 2014; Couch et al. 2019). With significant gains in students' Human-Centered Design (HCD) self-efficacy and parent and host feedback, we feel that leveraging Design Thinking was a valuable equity strategy for supporting youth outcomes and facilitating invention education. iINVENT leveraged Design Thinking to develop daily themes to make the steps of the invention process explicit. Research has also shown that leveraging design thinking and mentoring is an effective strategy for promoting an equitable learning environment for marginalized youth (Barton and Tan 2018; Couch et al. 2019). The assessment and stakeholder responses further support that claim.

A growing body of research points to the importance of providing youth active, open-ended projects that apply STEM content and skill in a context (National Research Council 2015). In an invention, the project's goal is to enhance the quality of life by creating something novel with value. We feel that Design Thinking and invention education adds a much-needed personal element to STEM education. Therefore, a strength of STEM content and skills framed as invention education may be that it allows youth to engage socially and emotionally because it focuses on the user and their quality of life to guide open-ended invention projects (National Research Council 2015). Lastly, invention education also pushes youth to think about bringing a product to market or adding to an existing product, and can be an avenue for economic empowerment (Couch et al. 2019).

Brokering with community hosts. Community hosts were able to reserve a suitable space and recruit youth effectively. Securing space and providing lunch were easier than recruiting the target audience (e.g., rural, low-income, Spanish speaking, first-generation college students). Hosts also expressed a considerable amount of program support and buy-in to recruiting youth they felt could most benefit from the program. Although the average camp attendance was 22 and most of the youth that attended matched the intended demographic, hosts still expressed hardship in recruiting youth and finding youth available to participate in the camp. While some hosts may have felt that recruiting 67% white students and only 27% Hispanic/Latino may not be a success, Oregon, as a state, is only 13.4% Hispanic/Latino and is 86% White (census.gov/quickfacts). In this instance, it may be necessary for organizations that rely on community hosts in distributed geographical locations to understand what success and diversity might look like in those community contexts. These conversations could help develop additional strategies or benchmarks for sustaining desired program outcomes.

Hosts also raised a few constraints in recruiting youth in rural areas. One host raised the issue of finding enough kids to fill camps when a small community has other youth activities. One of the goals of iINVENT is to promote access in rural communities. Being aware of other events occurring in that community can help ensure that the target audience is available to participate in the programs. The host’s feedback also raises concerns for the long-term growth of the program. In the case of iINVENT, the focus on rural—generally lower populated—areas planning around more significant events may help ensure program capacity and possibly grow the program in rural areas. However, due to the limited number of youth available, a rural program may benefit more from investing in the engagement quality than the quantity engaged.

Recommendations and Future Work

Design Thinking and invention. Design Thinking explicitly framed invention by creating daily themes (Empathize, Define, Ideate, Prototype, and Test). Based on the evidence, Design Thinking may have made inventing and the invention process more explicit to youth. Therefore, it may have called campers’ attention to the skills they were using and what they were learning, and shaped how they interacted at camp (Hand et al. 2013; Montgomery 2001). How Design Thinking can leverage instruction and youth outcomes still needs to be explored, but the approach is promising.

Near-peer mentors as users. College students acting as near-peer mentors and users for their invention projects were integral in supporting youth outcomes. Providing youth with a particular user group was essential for invention education to occur at iINVENT and for the camp experience. While the 2019 iINVENT mentor assessment is ongoing, all mentors expressed excitement in sharing what they know with youth, such as their majors, how they use STEM and design thinking, and their lives as college students. Mentors expressed they were excited to run camp activities and guide youth through their invention projects. Other design programs may want to think critically and creatively about how they can immerse a user group in the learning experiences, as it may be vital to supporting youth outcomes. Further documentation on how programs position youth to interact with mentors and how mentors interact with them will help address this ongoing issue. A possible avenue of inquiry could be how shared power and authority between the youth (inventor), user, and mentors shape the learning experience (Carroll 2014; Couch et al. 2019). This work could inform how mentors, or other types of support, help to develop, repair, or bolster youth STEM identity.

A deeper localized understanding. There is a need to understand why programs succeed more in some communities when compared to others. This work requires organizations to document and reassess their ongoing work and share successes and failures (Penuel 2017). For example, iINVENT data showed that camp attendance ranged from 8 to 33, and arranging transportation, while not required, was somewhat difficult for two hosts but not applicable for three. To OSU Program staff, this may seem like youth are not interested in the camp or transportation may be playing a role. However, that may not be the case or only part of it, as one host said, “Our biggest problem was that we have such a limited number of youth. The same week we had the following camps…” In this instance, the hosts and parents can help add context to the developing understanding when, where, and how learning opportunities can best be brokered in their communities to support underserved youth. This information is particularly important for planning programs that wish to work with specific communities for the long-term.

As educators and brokers enact unique research-based strategies for supporting youth, the documentation of the challenges, successes, and failures is needed, particularly in STEM education during out-of-school time (Barron 2014; National Research Council 2015; Penuel 2017). Evaluating Design Thinking and Community Hosts as equity strategies shows that they are useful in engaging and recruiting iINVENT’s targeted audience. In addition, including the voices of youth, hosts, and parents in assessment and evaluation of the strategies enacted illuminated how iINVENT can grow as an organization (e.g., recruiting Spanish-speaking mentors to contact families before camp and planning with community hosts around other local events). How youth-serving organizations can grow to best meet the changing needs of their communities is incredibly valuable to creating sustainable, impactful, and scalable programs that provide long-term support to all youth.

Adam Talamantes (Adam.Talamantes@oregonstate.edu) is a Program Coordinator for Precollege Programs at Oregon State University.

iINVENT is supported by funds from The Lemelson Foundation.

citation: Talamantes, A. 2020. Equity strategies: Community hosts and design thinking in a middle school summer camp. Connected Science Learning 2 (3). https://www.nsta.org/connected-science-learning/connected-science-learning-july-september-2020/equity-strategies

Curriculum Engineering Equity Inclusion Multicultural STEM Middle School Informal Education