Interdisciplinary ideas

Engaging and Empowering Students Through Choice

Science Scope—September/October 2021 (Volume 45, Issue 1)

By Katie Coppens

Student voice and choice is a term that emphasizes the value of personalized learning. According to Herold (2019), when it comes to personalized learning, “the idea is to customize the learning experience for each student according to his or her unique skills, abilities, preferences, background, and experiences.” Anstee’s 2011 book Differentiation Pocketbook focuses on choice enhancing the trust and respect between student and teacher while creating student ownership and engagement, which leads to increased motivation and success when clear parameters are established.

Background on choice boards

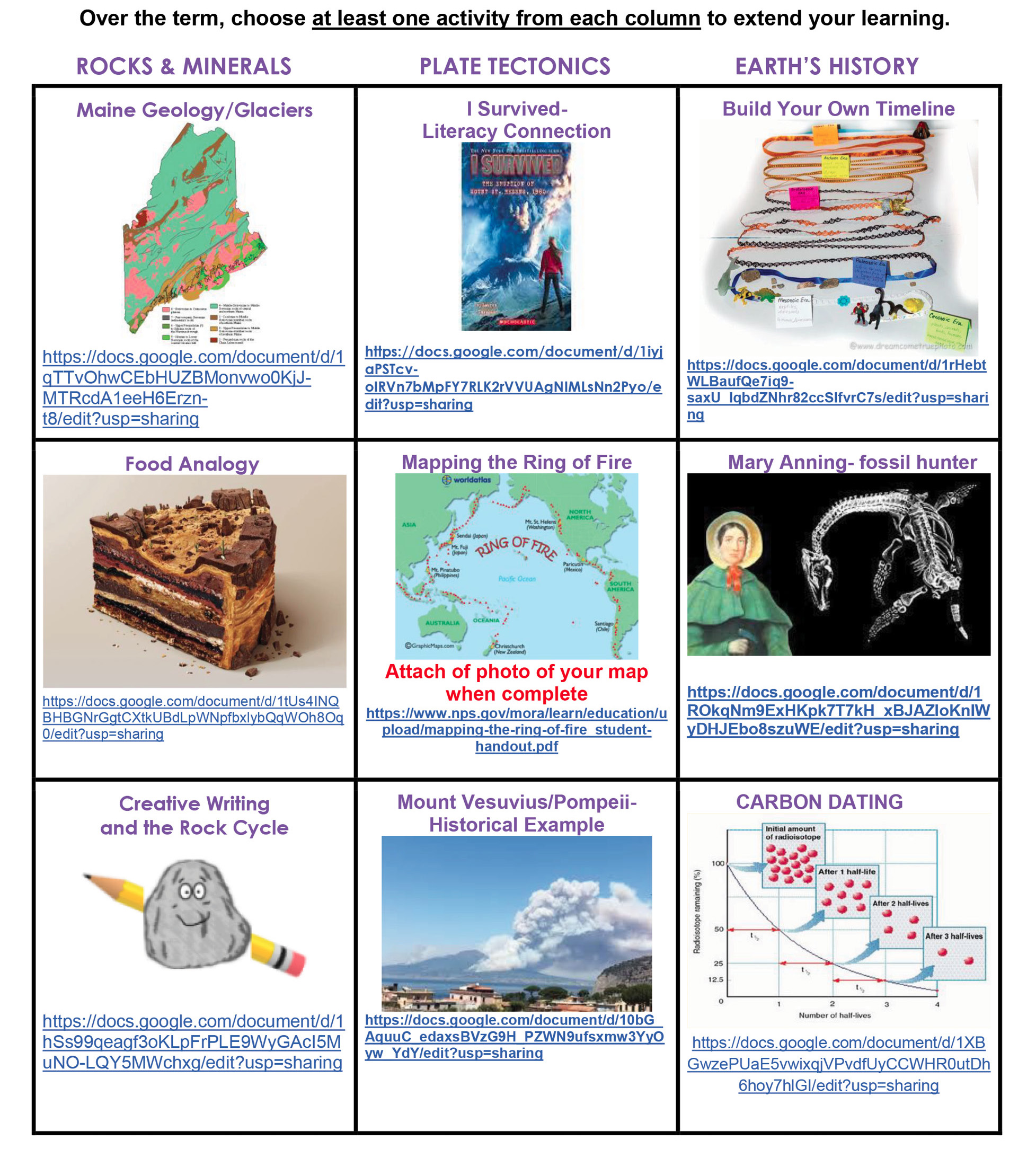

Choice boards are one of the simplest ways to implement voice and choice in the classroom by exposing students to a range of topics that extend their learning or provide various performance task options for the same concept or standard. In my sixth-grade science classroom, I provide all students with the common knowledge of a unit; then students have three options of how they’d like to apply and extend their learning. Over the year, some options connect to nonfiction reading, informative writing, creative writing, application to science-themed fiction books, data analysis, connection to a historical event, engineering, and art (see Figure 1; see also Intro to Newton’s Science Laws and The Ecology Choice Board in Supplemental Materials). For example, to start the year, we learned about the metric system. Students then apply their knowledge by either learning about echolocation or about the metric system in various Olympic sports, or collecting data on the distance that paper airplanes fly. Students have two weeks to complete the assignment and are required to complete at least one option. Many students choose more than one to complete.

The geology choice board.

Some of the options also do pre-teaching for upcoming units, such as the topic of echolocation, which comes up in our plate tectonics unit when they learn about Marie Tharp and Bruce Heezen’s mapping of the Atlantic Ocean’s seafloor. This approach of connecting current units to future units has the added benefit of providing students with opportunities to be leaders. For example, one of the choice board options in the geology unit was to learn about glaciers. Later on, in a plate tectonics unit, those students provided the class with an overview of glaciers, which helped when we discussed how glacial striations across continents serve as evidence for the theory of continental drift.

Introducing a choice board to students

At the start of any given unit, I show the choice board as a long-term assignment (which we call the unit’s “Challenge by Choice”), and I share the link to each assignment option in Google Classroom. I then explain which choices students could begin now and which ones they need to wait for as they acquire more background knowledge. Having the extension work during the unit, rather than at the end, has enhanced students’ engagement, our discussions, and student understanding of the unit. Students also enjoy sharing their learning experiences with others who choose the same topic. For example, for those who chose to learn about Mt. Vesuvius and Pompeii in the plate tectonics unit by watching a documentary and exploring an interactive website, I heard chatter at the start of class between students about one of the dramatic parts of the documentary. There’s always a buzz about the choices, which is enhanced by beginning class with a quick check-in about progress on their work. This also becomes a time for students to offer suggestions for others who chose the same topic.

In the 2020–2021 school year, when I taught much of the year as a mix of in-person and virtual learning, choice boards were particularly effective. Choice boards allowed students much-needed flexibility, individuality, and an opportunity to extend their learning in various directions. Choice boards could be an in-class activity, homework assignment, or long-term assignment throughout a unit. I used one choice board, the environmental issue action project, as a combination of all three. Students researched an environmental problem of choice, then chose to show what they learned through an informative art project that would be displayed, to write about the problem and their action ideas to stakeholders, or to do direct action about the issue. Choice was already built into which environmental topic they chose, but the choice board reflected various approaches to the final product of the unit. See the universal rubric for the choice board, which emphasizes the depth of knowledge and connecting concepts to our unit of study, in Supplemental Materials.

Enhancing student engagement

Anstee (2011) emphasized avoiding extensions that are more of the same, or MOTS as he calls them, and instead focuses on HOTS, or higher order thinking skills. To improve engagement and ownership, it’s vital that students feel these assignments are a valuable use of their time. Research by Thibodeaux, Harapnuik, and Cummings (2019) found that perceived ownership from choice, especially when seen as authentic learning, is an indicator of students’ engagement with their learning environment. In a survey of my 92 sixth-grade students about the use of choice boards in science class, 96% reported positive experiences with choice boards. Overall, the options create excitement about learning, and students voiced that they felt empowered by having a choice. These quotes from my student survey reflect the majority of students’ answers:

- “I like that I could choose what I wanted to do. I also liked learning something that went beyond class, like learning about glaciers—which are cool.”

- In this crazy world right now and with many things that I do not have my say in, this gave me a chance to make my decision.”

- “I like the variety, and how it has the major idea of what we are mainly learning about, but it also has an interesting alternative topic.”

- “It made me feel independent. I liked that when I finished one, I could do another.”

Although students were only required to do one of the options, many students did more than one assignment. Out of the three choices for our Earth’s history unit, 55% of the students completed one option, 32% completed two options, and 13% completed all three options. Although most students liked the independent pacing of two weeks to complete the choice-board assignment, a few students struggled with time management. For students who struggled, I chunked the assignment into smaller due dates. I also helped struggling students reflect on their interests and strengths before choosing a topic.

When designing the choice board for each unit, I worked with the other sixth-grade science teacher to develop ideas, which led to a variety of approaches to assignments. Because we collaborated on the choice boards, all students in the grade were working on the same assignments, which added to the conversations students were having gradewide about what they were learning in science. Using the same choice boards also created continuity across our classrooms in terms of learning experiences and unit organization.

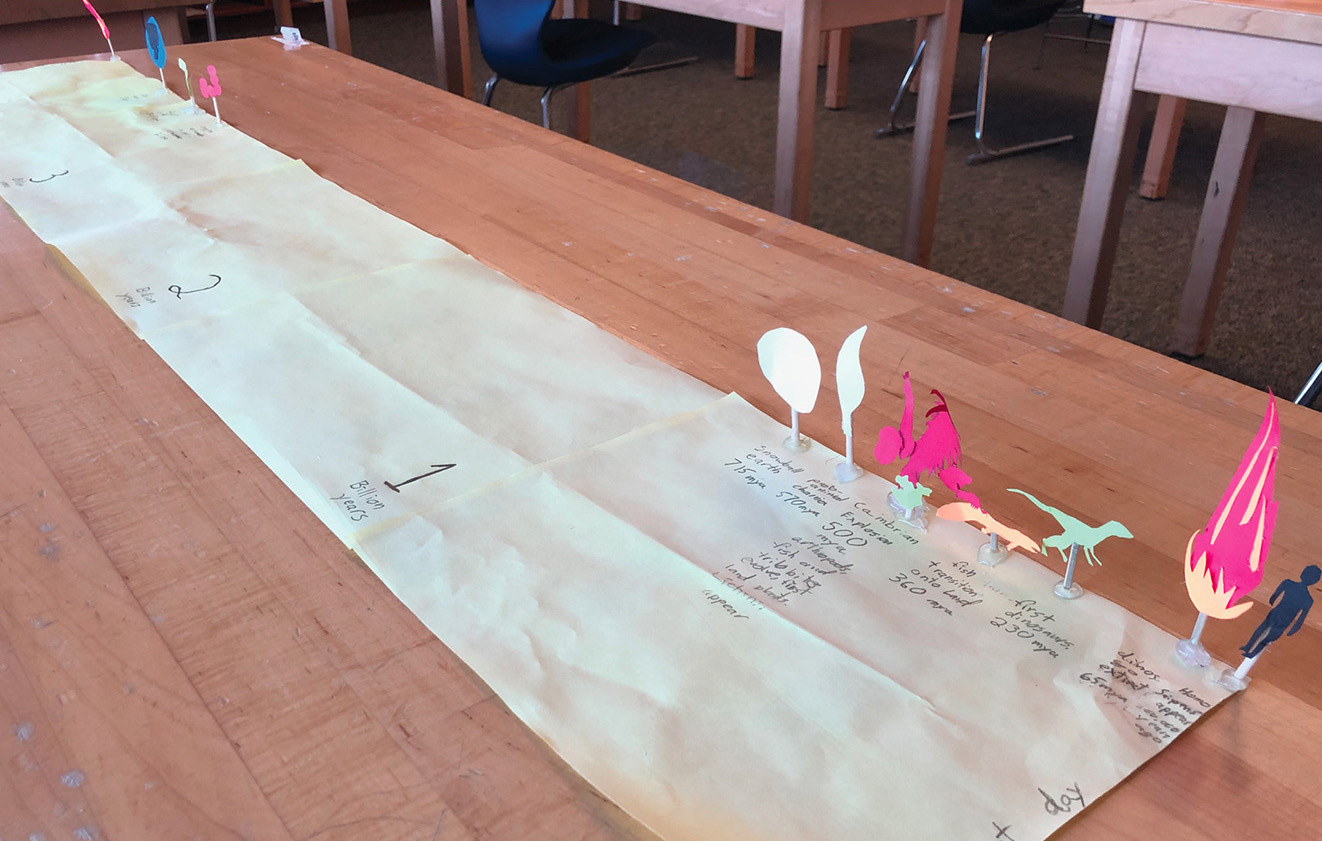

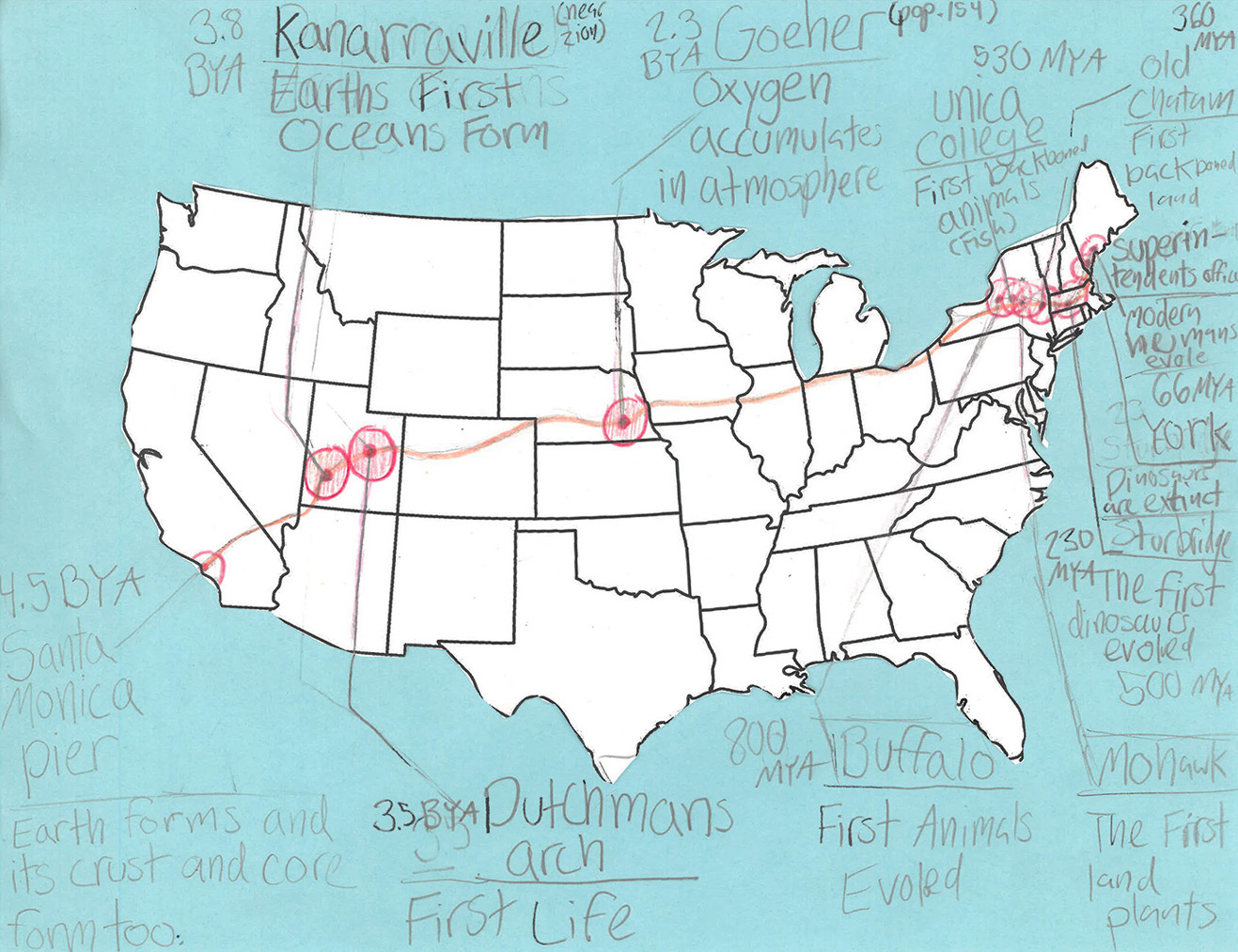

Out of all the benefits, the most significant is that voice and choice sets a positive tone in the classroom that embraces the endless application of learning and students feeling valued as individuals. For example, one of the Earth’s history unit options was making a visual timeline of Earth’s past. Figure 2 shows how an art-loving student visualized the sequence of events. Figure 3 depicts Earth’s history as a road trip that begins at Santa Monica Pier in California (when Earth formed) and ends at our middle school in Maine (current day). Each student conceptualized the events but did it in their own way after reflecting on their strengths. There is no presentation for most choice boards, but when students create something like a model, story, or song, I like to give them the option to show the class. When the student presented her map, she talked about how much math this took to complete and pointed out how crowded her road trip became around New York. When presenting, students become the teachers, and you can see their pride in how their work reflects their strengths, individuality, and knowledge of the topic. •

A student’s visual of Earth’s history through art integration.

A student’s visual of the Earth’s history through math integration.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIALS

Katie Coppens (contactkatiecoppens@gmail.com) is a science teacher at Falmouth Middle School in Falmouth, Maine. She is the author of NSTA’s Creative Writing in Science: Activities that Inspire and various science-themed books for children including The Acadia Files chapter book series, Geology Is a Piece of Cake, and Earth Will Survive, but We May Not.

Assessment Earth & Space Science Instructional Materials Interdisciplinary Learning Progression Performance Expectations Teaching Strategies Middle School Pre-service Teachers